From the Art Review Archive, Spring, 2024: Michael DeLaurier talks with the Review about meditation, house parties, and the transformative power of light.

Today, waste is pervasive. Explorations into oceanic trenches reveal plastic at the Earth’s lowest depths, nuclear waste produced in weapons manufacturing has a half-life of billions of years, and DNA testing reveals the imprint of industrial chemicals within the bodies of industrial workers. As this accretion of waste continues and production churns, institutional, legally-sanctioned, and culturally accepted responses to waste often fall short. Recycling systems cloak continued plastic production in a veil of sustainability, standards for workplace chemical exposure vary dramatically between countries, and landfills capped by concrete quietly leach into adjacent land. Even the systematic structure of molecular identification of chemicals fails to capture their dynamic interactions and nuanced impacts in real-world scenarios. In myriad ways, waste exposes the limits of scientific knowledge, but industry is quick to accept this limited understanding as comprehensive. Industry-influenced legislation claims scientific authority, professes “control” over chemicals and best-practice management, but current standards do less to protect communities and more to sanction continued production of hazardous materials with limited understanding of associated risks.

As corporate capture corrodes the capacity for scientific research to address chemical threats, new modes of understanding must be propagated to expand avenues for effective response and remediation. In recent years, an emerging cohort of contemporary artists has increasingly centered waste, chemicals, and pollution in their studio practices. Perhaps these artistic practices can play a role in a critical network of rhizomatous environmental knowledge development. To better understand the role that environmentally engaged artmaking can play, the Brown University Art Review conducted a series of interviews this past spring with Julien Creuzet, Jorge Otero-Pailos, and Max Liboiron, all of whom engage directly with chemical waste products as they exist in today’s environment. The excerpts included in this text were edited for clarity.

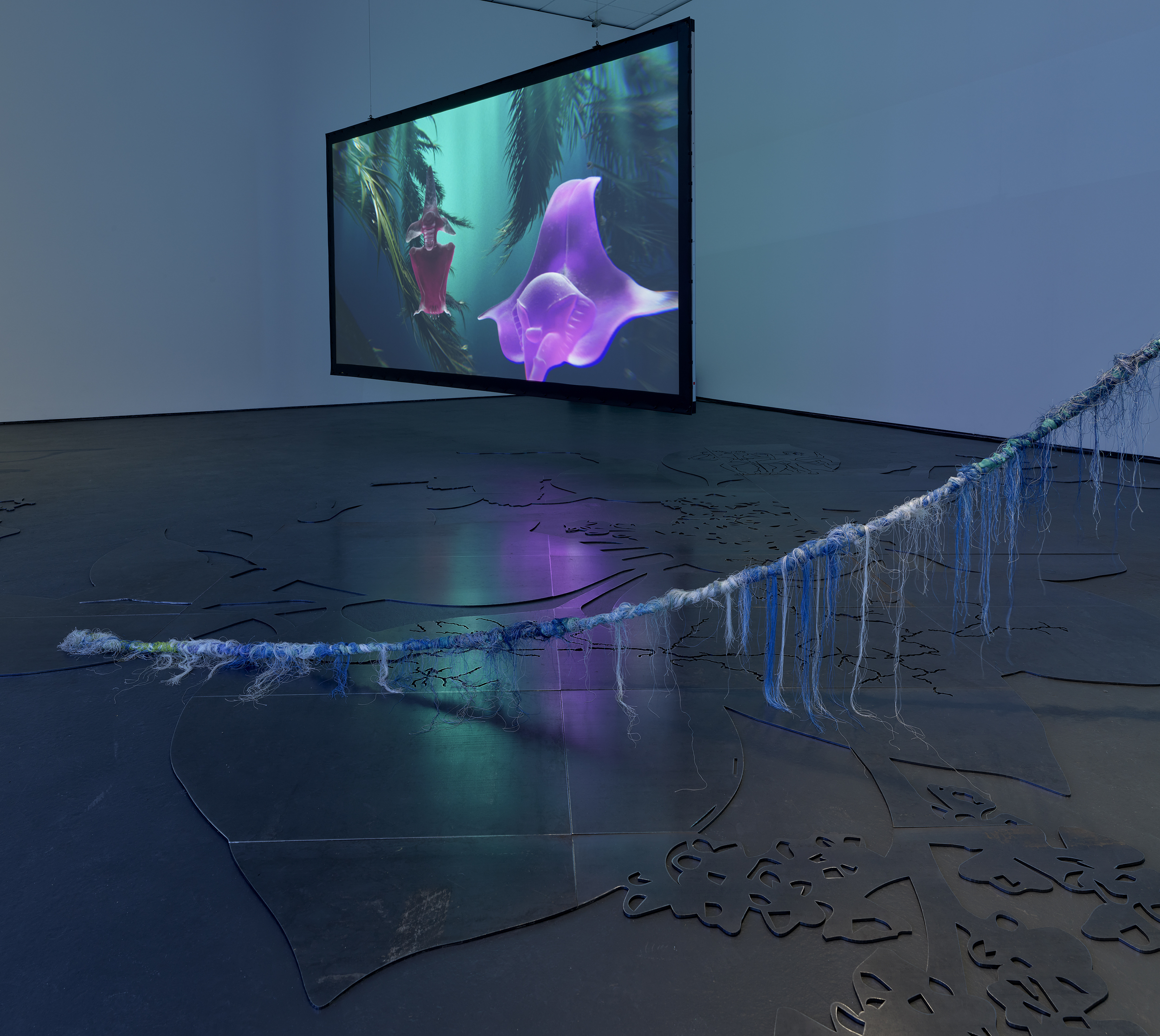

This spring, Brown’s David Winton Bell Gallery underwent a comprehensive transformation. As the gallery doors opened, visitors were met with an atmospheric installation of sound, light, and rich visual stimuli titled Attila cataract your source at the feet of the green peaks will end up in the great sea blue abyss we drowned in the tidal tears of the moon (2024). This world, crafted by French-Caribbean artist Julien Creuzet, is dominated by water. The gallery was dimly lit, with most light emanating from four screens suspended in the space. Each projection presented an underwater tableau. Seagrass flowed in gentle currents as light filtered down from above. Six floor sculptures formed an archipelagic landscape whose metal surfaces reflected the blue-green hues of the projections above. A translinguistic soundscape created by Creuzet filled the space with six original audio tracks, largely in creolized French.

Raised on the island of Martinique, Creuzet’s practice explores the nuances of postcolonial identity and the transatlantic slave trade in the French Atlantic. Throughout much of his work, Creuzet centers water as a fundamental space connecting islands, countries, and economies. The Atlantic, reimagined in Attila Cataract (...), represents a site of deep traumas and liberating futures. But it’s not just water filling Creuzet’s carefully crafted spaces. Plastic emerges just as pervasively. In the Bell, a glowing projector revealed a sea turtle struggling against fishing nets. Plastic shopping bags imitated jellyfish, and crushed bottles floated across the screens. Eight sculptural forms hung in the space, delicately layered with rich texture and color. A close look at these forms revealed massings of synthetic fibers— warped plastic. Pollution surfaced throughout this exhibition, prompting critical questions. How did it get here? How did it get so bad? And what do we do now?

When considering plastic’s emergence in his practice, Creuzet responded thoughtfully, describing how “this type of petrochemical material is really interesting. Normally, the idea is not to produce any more of these petrochemical materials, because they take such a long time to disintegrate in nature. [But what] does sculpture mean in a Western context? [It exemplifies] this idea of a long temporality, of surviving for eternity inside the museum. When you start to work with materials which take thousands of years to disintegrate in nature, [it begins to reflect these archetypal sculptures], existing the same way as these [sculptural] marbles, bronzes, etcetera. In a certain way, they have the same function. [They might be plastic, but they’re] not sculptures to go to the garbage, [they become] something to protect, to collect. It can give an idea of the social context where I am from, a social context of my identity, my human perception, of my human reality. The sculpture plays with that.” This idea raised by Creuzet, of long temporality being a key quality shared by sculpture and plastic, warrants further consideration. Sculpture, as conceived by European centers of power, represents an enduring, physical manifestation of historical achievement, of progress, power. What does it mean to offer plastic debris as an alternative embodiment of this same historical legacy? Strikingly, alongside the plastic bottles, bags, and fishing netting, two iconic sculptural symbols floated suspended in the blue-green waters on Creuzet’s large-scale projections. One of these sculptures is Jacopo Sansovino’s Neptune (c.1554–67), sculpted for Doge’s Palace in Venice as a symbol of Italy’s dominion over the sea. In Julien’s projection, this powerful symbol is inverted: what may be tears stream from his stone eyes.

In a critically diasporic lens, this sculpture stands on par with waste, both of which serve as physical artefacts of colonial legacy’s imprint upon colonized territories. As European powers entrenched systems of dominance, not only did they leach resources from global territories, they concurrently established directional flows of waste. Those living in the global north benefit from the export of waste (and the export of chemically intensive manufacturing processes), into the global south, whose populations continue to face the greatest burden of exposure. “I think [that] it's part of my epoch, and it brings critical information. I like that you can change [perspectives] of what [belongs] in the garbage and what [warrants] conservation, [that which is considered] art. It’s about colonialism, about capitalism, and how these two worlds are connected. We need to think about current conditions, and [when] considering what materials can represent this context and this history, I think you can include plastic. The distinction is I make a sculpture, and sculpture is a certain consideration of beauty. It's not necessarily something you like or something you desire, it can be a rejection, It can be like a frustration. It can be beauty, or something you hate.” Within Attila Cataract (...), pervasive plastic typifies destructive legacies of colonial advancement. To represent Martinician experience holistically, plastic must be included. This pollution represents historical legacy more accurately than any grandiose sculpture can. Attila Cataract (...)’s centering of waste, then, represents a pointed recentering of pollution in conversations considering colonial impact in the French-Caribbean landscape today.

Jorge Otero-Pailos is another contemporary artist whose practice centers waste. Otero-Pailos is an architect, architectural preservationist, theorist, educator, and studio artist. Otero-Pailos approaches waste from a critical perspective similar to that of Creuzet and, interestingly, his work has interrogated one of the same historic precedents as Creuzet’s Attila Cataract (...): Venice’s Doge’s Palace. The work, The Ethics of Dust: Doge's Palace, takes the form of a floor-to-ceiling sheet of latex. This translucent sheet, illuminated from above, reveals an intricately detailed impression of one of the palace’s stone walls.

This intervention in Doge’s palace is not purely sculpture, nor is it a Trompe-l'œil, instead, this tapestry-like installation is the product of a process of architectural preservation. For The Ethics of Dust series, Otero-Pailos identifies “dirty” walls within historically significant sites which have escaped the aggressive cleaning typical of preservation processes. Otero-Pailos then coats these monumental walls with a layer of latex which, once dry, are carefully peeled off. As they are removed, these sheets take with them a layer of grime, dust, and soot. In some cases, this “dust” represents centuries of accumulated pollution. By working concurrently as an artistic work and as a legitimate process of preservation, The Ethics of Dust is granted intimate access to invaluable sites of cultural heritage.

Critically, this project doesn’t just preserve buildings, but also the pollution which once coated them. Otero-Pailos explained his interest in preserving pollution itself, how “dust, in particular, has been very important because it is [often] considered something that is detrimental [...], so it is [typically] removed from architecture, but it has a very important story to tell about [...] our collective industrial impact on that built environment. I've been developing creative ways to try to preserve that dust, so that we can continue to make sense of it collectively.” Otero-Pailos describes this practice as belonging to a movement of experimental preservationists, a group who work creatively to expand the scope of contemporary preservation efforts. Historically, the field of preservation emerged in order to preserve sites of cultural heritage, “preservationists recognized that these objects, especially architecture, even places, are shared. [...] These are shared objects through which many of us make sense of our lives [and cultural contexts], so we have to pay attention to them, and we want to pay attention to them so that we can continue to make sense of our lives through them. [...] Even though they might be owned by a private individual, there is a collective investment in them, a collective recognition of their value and importance.” Architectural Preservation efforts typically focus on the building or district-level. Experimental preservationists, on the other hand, push “against the idea that the unit of analysis of preservation should be the single building. [...] They look at, for example, the process of material transformation, materials that become buildings and later cease to become buildings. [Or,] they focus on the social realities that are related to the built environment, which has been a significant shift. It means that people are more interested in questions not simply of “embalming” the thing to be preserved, but actively engaging in it, transforming it, [...] and giving it new value in the contemporary world. [Creative acts are] at the core of this experimental preservation movement, where people are really trying to use creative practice to save those things that they considered valuable in the built environment.” By preserving more than buildings themselves, the experimental preservation movement seeks to situate cultural artifacts within larger sociocultural and environmental contexts.

So why dust? Why might the pollution accumulating on buildings warrant preservation as a cultural artefact? Otero-Pailos doesn’t see a building and dust as representing disparate histories, describing how “dust comes from the building. You know, most of that dust is either literally falling off the surface of the building as the buildings degrade, or the dust is the product of materials consumed in order to keep a building functioning, such as coal or oil. You cannot have architecture unless you are consuming those materials. Architecture is a form of material consumption, [whether it’s] the wood used to build [them], or the concrete, or the steel, each of them has an output, you know, an, “externality” that becomes ignored.”

Otero-Pailos goes a step further, describing how “Architecture itself makes [waste] invisible. [...] I did a project with Louis Vuitton, at the original house of Mr. Louis Vuitton, who lived next to his factory. The house was black from soot for many years, because the smoke from the factory would fall right on the house. When LVMH bought Louis Vuitton, they cleaned up the whole house, but there was a garbage shed attached to the house, so they couldn’t clean [the wall underneath]. That shed quite literally hid the garbage and hid the pollution. So I was able to cast the garbage shed, to pull the original 19th century pollution from it. A lot of architecture, in terms of their design, their organization, and the material choices that are made, are meant to hide waste. For example, most modernist buildings use materials that are supposed to be self-cleaning, especially on the facades. [This trend started] with glazed terracotta, which didn't work, the pollution still stuck to it. Plate glass, chromed materials, lead paints, titanium paints, etc, are meant to be resistant to dust. All of these materials try to appear as if [they evade environmental impact], they're meant to appear new, fresh out of the factory, forever. These materials replaced masonry and other materials that absorbed soot, and they were considered great because they didn't [reveal the] smoke [in these heavily polluted] cities. Now, even as [...] air pollution continues, we still build these glass buildings, this architecture [which] essentially acts as if there's no environmental reality out there. We have very sophisticated maintenance programs [to keep up this appearance of purity]. Look at the window washers of New York, they are at work all the time.

“What I'm trying to do is to bring it back into our field of vision, because we could not have that architecture unless we made that pollution. It’s important for us to be able to deal with it as a culture instead of continuing to act as if [pollution doesn't] factor into the production of architecture. It's difficult, because we don't have a way to make architecture without burning oil, without burning coal.” For context, between material production (steel, concrete, iron, aluminum) and building operations (heating, cooling, etc), the built environment is responsible for a staggering 42% of global CO2 emissions annually. Beyond this direct contribution, the assets financing the monumental historical By preserving evidence of this externality at monumental scale, The Ethics of Dust ensures that pollution’s centrality to the built environment remains visible.

In Creuzet’s practice, waste surfaces in French-Caribbean diasporic experience; in Otero-Pailos’, it collects upon stone monuments over centuries. Though these parallel practices center vastly different subjects and utilize wildly different artistic media, both Otero-Pailos and Creuzet work towards similar aims. Not only do these artists reveal the pervasiveness of waste in their spheres of interest, they illuminate the extent to which this waste originates from historic and continued structures of power and development.

The final interview I pursued when developing this article was with Dr. Max Liboiron (Michif-settler, they/them). A professor, activist, and scientist at Memorial University of Newfoundland. Liboiron (whose work I’ve cited earlier in this article) conducts research concerning plastic pollution. In addition to their research, Liboiron pursues anti-colonial, feminist, and Indigenous research practices as the founding director of the Civic Laboratory for Environmental Action Research (CLEAR), an interdisciplinary plastic-pollution lab space which pursues anticolonial research methodologies dedicated to good land relations. My interest in speaking with Dr. Liboiron stemmed from a misunderstanding. I’d heard that in addition to their research, anticolonial work, and teaching, they pursued an art practice concerned with pollutants. I was excited to speak with them because their experience promised a unique perspective situated between these two worlds of scientific and artistic knowledge I’m interested in. Upon contacting Dr. Liboiron, I was surprised to learn that they are “not a practising artist anymore (not for over ten years) and in fact have removed [their] art from [their] website because [they] don’t think it does the work that needs to be done or frame things the way things need to be framed, at least for political work around environmental harm. [...] I may not fit the ideas you’re looking for.” This was an unexpected response, but Dr. Liboiron’s experience also promised an opportunity to challenge the conclusions I was beginning to draw concerning art’s power in environmental discourse. I had questions.

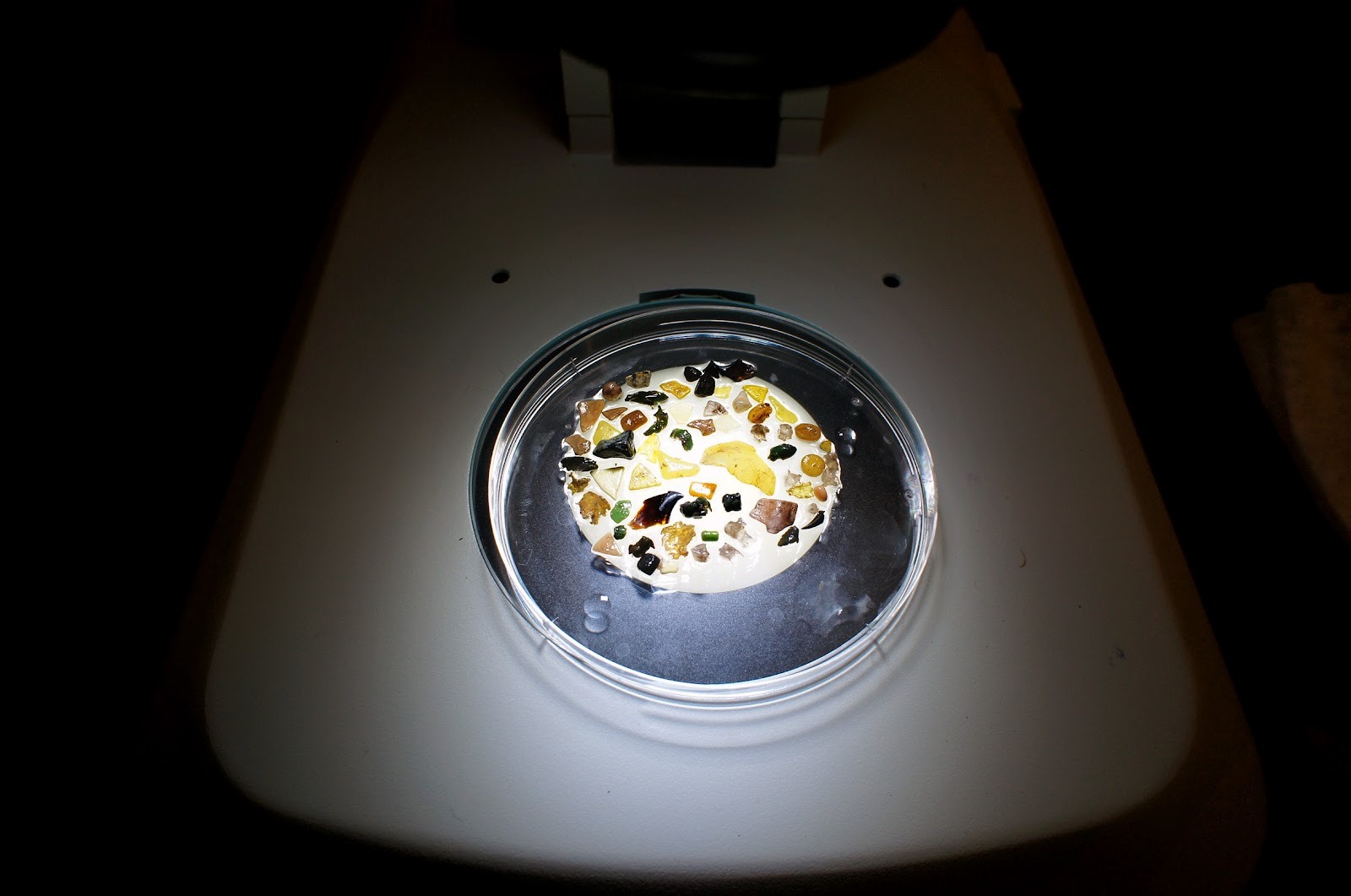

For context, Dr. Max Liboiron did formerly pursue an art practice. As they describe it, their work was focused on “the environment and the impact that culture (like colonialism, scienceism, universalism) had on the environment. Often, this [work] was a critique of Nature with a capital N as an ideal environment without humans.” Liboiron’s practice spanned media including printmaking, photography, and large-scale interactive installations. Some of their artistic works directly concerned their experience in plastics monitoring, like “a marine snow globe that included plastics, and a few photographic series of samples from [their] lab including a series called Plastic is Land. Both were meant to show how plastics are part of landscapes now, including how hard it is to tell plastics apart from organic materials. And that this is the starting point for theories of change whatever they may be.” Liboiron describes how these plastic works were “based entirely on my research of the emerging field of plastics monitoring, and the last few suites of photos I did were of actual samples from my scientific monitoring work. So [...] my art was a type of research outcome.”

But art-making wasn’t working for Liboiron. Although this work sought to complicate framings of landscape as “pristine,” instead “both [plastic] pieces are consistently interpreted as ‘Oh no, plastics are everywhere, bad, bad, bad’ rather than as part of environments, no matter how much structuring [Liboiron does] to influence interpretation. This means [plastics] get used in ways that blame consumers (even though only industry produces plastics), in annihilation-ist theories of change (fuck all plastics!), or in ways that contribute to charismatic terribleness that leads to apathy or sorrow (there’s plastic everywhere, there’s nothing we can do). None of these help with theories of change.” The inherent presence of subjectivity in art interpretation undermines its ability to communicate critical perspectives in the face of dominant environmental narratives. In terms of plastics, the critical reframing which Leboiron hopes to foster is shifting the onus of responsibility from the consumer (i.e. “Reduce, Reuse, Recycle”) to the producer (i.e. removing subsidies from oil). But “because the interpretation of art is so very much up to the viewer [...], the dominant narrative just ate the intentions alive. It may have been that I just wasn’t a good enough artist to communicate nuances against the grain, but there are some pretty great plastic artists out there [who] I see the same thing happening [to]. Science has a much stronger ability to be understood in specific and intended ways— there is a right and wrong way to interpret things, unlike art— so [science is] just better suited to changing a dominant, charismatic narrative.” Moreover, art might not even reach the audience best suited to enacting positive environmental changes. “Art and science have totally different audiences. And the audience for science (knowledge infrastructures, policy makers, other scientists, international bodies like the UN) are much, much better suited to change, particularly the theories of change I subscribe to.”

More critically, Dr. Liboiron’s shift away from artmaking represented broader qualms with the art world, which is itself deeply rooted in the same structures of colonialism and capitalism which proliferate environmental harm today. Leboiron described how “the Art World, by which I mean the professional art world of galleries, contracts, shows, sales, etc, is hyper individualistic (the Artist is genius trope, or insight and knowledge comes from an individual rather than a collective of experiences), and hyper individualism is one of the hallmarks of colonial culture. [...] Honestly, anything that is solo-authored at this point, whether art or science, just can’t deal with the complexities of what’s happening and how to make change given the diversity of situations and nuances, and art is one of the last holdouts of extremely individualized knowledge production out there.” Moreover, Liboiron sees environmental work as being intrinsically tied to anticolonial work. In their view, this critical work isn’t likely to happen in the art world beyond asking “people to stop appropriating Indigenous designs, symbols, cosmologies, etc. I also am adamant that decolonial means Land Back. I don’t think decolonization has anything to do with inclusion, such as including Indigenous peoples in shows, contracts, etc. Which means that the most decolonial thing the Art world could do is turn to its friend the Museum world and repatriate Indigenous cultural items.” Ultimately, after abandoning their art practice, Liboiron hasn’t looked back. “As a scientist who used to be an artist, I find that the science I do is much better at getting to the nuances of plastic pollution and theories of change based on Indigenous sovereignty, harm mitigation, Plastics Treaty work (and other policies), place-based problem-definition and thus solutions, and infrastructure rather than awareness or righteousness.”

As Dr. Liboiron aptly diagnosed, art itself isn’t immune to the corrupting influences of capital and industry. The capital-A Art World is highly commercialized, and to a large extent, capital-A Art is an artifact of the same colonial legacy which established structures of environmental harm and injustices persisting today. In a context of continued corporate capture of environmental knowledge, self-critique is essential to pursuing meaningfully disruptive art practices— particularly those concerned with the environment at their core. Definitions of art and the scope of artmaking practices are constantly evolving, undergoing self-critique, and adapting in response to changing contexts. The creative core of these endeavors lends them a unique opportunity to adapt and— critically— to alter and reimagine themselves. Though the process of critique is not unique to artmaking, art does maintain a unique level of fluidity, offering great opportunity for adaptation. Despite systematic and intrinsic flaws, these qualities help maintain my cautious optimism that art can meaningfully respond to unprecedented environmental challenges.

I’m deeply appreciative of Dr. Liboiron’s thoughtful and critical insights, and I’m compelled by their arguments. As someone who’s deeply inspired by the change-making power of art, I initially feel resistance to critiques which in some ways challenge the very foundations of artmaking itself. I’m hesitant to wholly abandon my belief in art’s potential— Creuzet and Otero-Pailos, for example, both have practices which, to me, embody the unique strengths of this form of communication. Otero-Pailos’ work speaks to art’s ability to nimbly traverse oftentimes siloed fields. The Ethics of Dust pulls conceptual grounding from fields including environmentalism, architecture, preservation, urban studies, and cultural heritage studies. In doing this, Otero-Pailos complicates arbitrary boundaries historically set between these fields, offering uniquely interdisciplinary opportunities for engagement and problem-solving. His The Ethics of Dust series’ title references a written work by John Ruskin, The Ethics of the Dust. Ruskin, to Otero-Pailos, exemplifies a cohort of “19th century [...] preservationists that thought environmentally, that didn't see divisions between architecture and the environment. All of them were brushed aside by modernists, because they were considered to be too concerned with the past, with tradition, with emotion, with connection to the environment.” Otero-Pailos believes that “revisiting figures like John Ruskin [can] encourage a more synthetic and all-encompassing view of architecture as an art, as an act of care, and as something that is connected to a continuum of realities that go beyond the hyper-local of the site.” Otero-Pailos’ work does just that, continuing a legacy which centers critical flow between built and natural systems.

Concurrently, Creuzet’s practice typifies artmaking’s diverse avenues to pursue understanding: sculpture, video, light, sound, written word, even performance and choreography. This highly interdisciplinary practice generates a body of work which is approachable from a myriad of access points. Moveover, Creuzet’s practice begins to escape the hyper individual impulse which the Art World oftentimes perpetuates. In entering worlds of video, performance, and music, Creuzet works with a community of creative collaborators spanning choreographers, 3D rendering artists, scenographers, musical compositionalists, performers, and sound engineers. For example, a performance in Brown’s Lindemann performing arts center marked the opening of Creuzet’s spring exhibition. This work, Algorithm ocean true blood moves, featured vocalist Malou Beauvoir, bélé drummer Boris Percus, and music (the Martinican dancehall genre Shatta) composed by musician Natoxie. Movement in the performance was choreographed by Ana Pi, and was performed by a team of dancers from The Ailey School. In this way, Creuzet’s work is deeply enriched by a creative community spanning media, creative perspectives, and lived experiences. In addition to these strengths, the highly critical nature of both Creuzet and Otero Pailos’ practices inspires my belief in the import of this work. Both of these practices push boundaries, resist simplistic or siloed readings, and offer complexly layered access points from which to better identify and historically contextualize waste today.

Thank you to Julien Creuzet, Jorge Otero-Pailos, and Dr. Max Liboiron, all of whom were incredibly generous in sharing their insights and time in support of this article.

(Cover Images, from left to right: [Julien Creuzet, © Magasin CNAC. Photo: Pascale Cholette], [The Ethics of Dust: Alumix, Exhibited at Manifesta 7 European Contemporary Art Biennial (2008), via oteropailos.com], , and [Dr. Max Liboiron. Image credit: David Howells, via participatorysciences.org])