TikTok-star-turned-RISD student, Camila Salinas, discusses the evolution of her self-portraits through the pandemic, internet stardom, and art school. She reflects on authenticity, the impact she hopes her work has on viewers, and the legacy she’s beginning to build as a young artist.

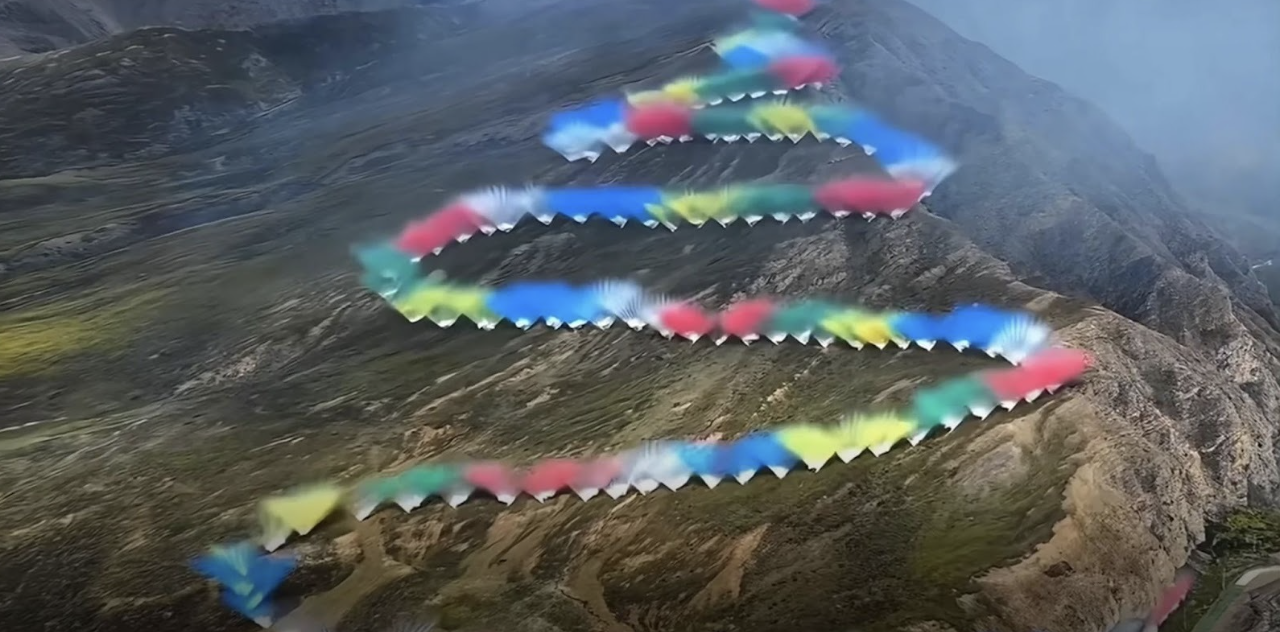

On September 19, 2025, Chinese firework artist Cai Guo-Qiang, paired with the outdoor apparel brand Arc’teryx, set off a promotional campaign. The Rising Dragon was set at an elevation of over 5,500 meters in the Tibet Shigatse region. This campaign was delivered through land-based installations: after the artist arranged the lighting of the fireworks, a “dragon” made of mixed-colored fireworks ran along the mountain ridge in a convoluted path. In one video, some sparse, mushroom-like smoke rose from the ridges, then developed into fuzzy explosions with radiating orange-red, climbing up the mountain. In the video, people were clapping, amazed by this mesmerizing visuality and its stunning ephemerality. However, as the last string of smoke disappeared on the plateau, concerns and criticism immediately arose. The netizens were saddened and disappointed by the artist and the brand’s ignorance of the long-term, hard-to-measure damage inflicted on the fragile Himalayan ecosystem. The perfunctory agreement between the team and the local political party further irritates people, as it claims that the fireworks and their remnants are biodegradable and eco-friendly, and that the entire process is monitored.

Cai sees this large-scale art practice as a realization of his 1989 work, “Ascending Dragon: Project for Extraterrestrials No. 2,” in which he uses durable paper, drawing with gunpowder and ink — what we see as black brushstrokes are actually “residues of fire.” The work eventually shows a dragon scaling a mountain to heaven. Yet, no one would imagine that the dragon — an imaginary, archetypal symbol of China — would present itself as the luxury outdoor brand’s visual campaign.

However, Cai’s Rising Dragon in the Himalayas eventually doesn’t appear as a simple revisit of his earlier work. Rather, the two works diverge sharply in medium, audience, and intention. In Cai’s original piece, the dragon symbolized the power of nature on earth and in the universe. The coarse brushstrokes and dotted ink claim blank spaces unrestrictedly, showing an ever-changing liveliness and brimming emotions. A longing to fly freely through the skies and oceans beyond physical limitations is therefore expressed in a deeply human way.

Now, as the fire dragon ascends in the Himalayan air, what was once a meditation on humanity has become an ambition in the Anthropocene — our will to command the sky, the landscape, and even fire. The original message has been flattened into an image of a corrupted commercial power: the cosmic yearning of the earlier work collapsed into an image of control. The transformation that occurred on the spiritually and environmentally charged Tibetan plateau mirrors a broader pattern in contemporary culture: the commodification of the sublime.

While The Rising Dragon enraged people with its environmental insensitivity, it also brought Cai’s long-standing artistic paradox to the forefront. His art has always grappled with the tension between destruction and creation, permanence and disappearance; yet when that abstract language of gunpowder, paper, and ink erupts into a living landscape, more is at stake than visual spectacle. The Himalayan plateau, an ecosystem and cultural terrain that existed undisturbed long before Cai’s practice, becomes the canvas, witness, and casualty. By using natural energy to create his imagined “primordial chaos,” Cai’s practice edges toward self-contradiction: the very forces he once revered as vital and generative now risk eroding the delicate order of nature itself. In earlier gunpowder drawings, the explosion was contained and marked on the paper, not land. But in The Rising Dragon, the space is open and invites a broader audience: not only the applauding spectators and the brand’s global viewers, but also the local communities, the high-altitude ecosystem, and the startled animals of the plateau. Are they, too, meant to be impressed by this “primordial state of chaos”?

To understand the cultural and ecological tensions in The Rising Dragon, it is essential to situate Cai Guo-Qiang within the lineage of land art. Land art emerged in the late 1960s as a new artistic practice that explores the potential of landscape and the environment as materials and sites for art. Early land artists, such as Walter de Maria, Agnes Denes, and Nancy Holt, sought to engage with geological time, spatial perception, and the physical scale of the earth itself. Land art emerged partly in resistance to the commercialism of the gallery system, seeking instead a direct, phenomenological encounter with the environment. The works that define this movement often rely on duration, weather, and the viewer’s bodily presence to complete their meaning.

Among these works, Walter de Maria’s The Lightning Field offers an illuminating comparison to Cai’s Rising Dragon. Located in a deserted area of New Mexico, it comprises 400 polished stainless-steel poles installed in a grid array measuring 1 mile by 1 kilometer. Like Cai’s project, it creates a human-made geometry within a vast natural landscape, inviting viewers to contemplate the encounter between artifice and elemental force. Yet the two works diverge sharply in how they engage nature and time. De Maria’s field embodies a quiet tension between precision and unpredictability between the strict order of the grid and the uncontrollable arrival of lightning. This subtle, restrictive force both contains and reveals the volatility of the sky — it does not merely overdramatize the scale of nature and the insignificance of humans before it, but also silently gestures toward the profound inherent order of nature, the rhythms and harmonies that make us stop and ponder. This work channels natural power, but it does not command it; it induces rather than forces nature’s participation.

In contrast, Cai’s work forces a response from nature. The Rising Dragon uses nature as a canvas rather than a collaborator, flattening the Himalayan Plateau into a surface on which fire and smoke painted a dramatic anthropogenic mystery. While both firework and lightning convey ephemerality, their temporalities differ profoundly. De Maria’s piece unfolds slowly, meant to be experienced over hours or even days. According to Dia Art Foundation, which maintains De Maria’s installation, “A full experience of The Lightning Field does not depend upon the occurrence of lightning, and visitors are encouraged to spend as much time as possible in the field.”2 This work therefore preserves the agency of nature — its silence, its refusal to guarantee a spectacle, yet generous, with its invitation to all kinds of experiencing and viewing.

If The Lightning Field invites appreciations of nature’s agency, The Rising Dragon exposes what happens when that agency is overwritten. What appears to be monumental and spectacular — the flashing cameras, the exploding fireworks, and the excited applause of the crowd — conceals a longer, quieter story of harm. In Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, Rob Nixon defines slow violence as “a violence that occurs gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all.” Cai’s explosion, although brief, deeply integrates such violence: the gunpowder residue left in soil, the displacement of wildlife, the carbon dispersed into the thin Himalayan air. None of these effects can be simply measured or undone through biodegradable materials, regulatory assurances, or a corporate apology. Violence, in this sense, is relational: the artistic pleasure for some eventually becomes a slow injury for others, whose sense of being and security heavily depend on this plateau and its inhabited life.

Finally, reading this from an ecofeminist lens, Cai’s practice reveals a distinctly masculine orientation toward nature: conquering, singular, defying reproduction; in contrast with the ecofeminist worldview of care, independence, and renewal. Cai’s art eventually turns nature into a stage of human aspiration, rather than a participant in shared reckoning, revealing how artistic endeavors can reinforce some of the hierarchies that other land artists seek to undo.

(Cover Image: Cai Guo-Qiang, The Rising Dragon, 2025. Gunpowder and colored smoke over the Himalayan Plateau via SIXTH TONE)