Analyzing how the techniques used in the earliest cave paintings reveal insights into human creative development and form the foundation for later artistic expression.

When I hear "Norman Rockwell," I immediately think of classic Americana. We see the artistic legacy of Rockwell in modern culture that directly reflects this image of America: Rosie the Riveter, his allegorical figure who became a cultural symbol of women’s strength during World War II, remains widely recognized, and his paintings continue to sell for record-breaking prices. Norman Rockwell was born in 1894 in New York, where he studied at institutions including the Chase Art School (now the Parsons School of Design), National Academy of Design, and Art Students League of New York. Rockwell's collection of over 4,000 works created throughout his lifetime (1894-1978) are embedded with this theme of American idealism, making his work the face of American culture during the wars of the 20th century and beyond. His paintings graced the cover of The Saturday Evening Post for decades, depicting an America of small-town values, family gatherings, and patriotic unity. Yet, as we see toward the end of his career when he joined Look Magazine in 1964, Rockwell left behind his archetypical depictions of American life and began to depict America more honestly, an America that looked radically different from the one that made him famous.

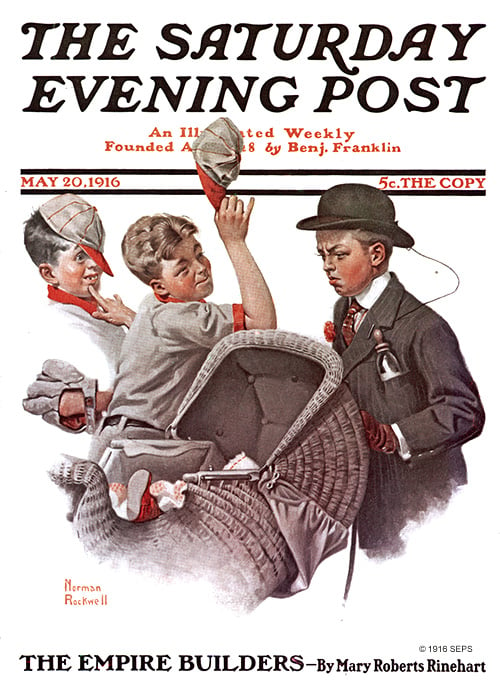

Rockwell is best known for his platform as an illustrator at the Saturday Evening Post, an American magazine popular in the 20th century, with around six million subscribers by the 20th century. Rockwell started working with the Post in 1916 when he was 21, with the Boy with Baby Carriage being his first official cover of the magazine. His paintings appeared on Saturday Evening Post covers more than 322 times over nearly five decades, most depicting everyday, candid moments of American life: diner scenes, children at the doctor’s office, and young couples on their first dates. These illustrations depicted America just as it wanted to be seen: fundamentally decent and innocent.

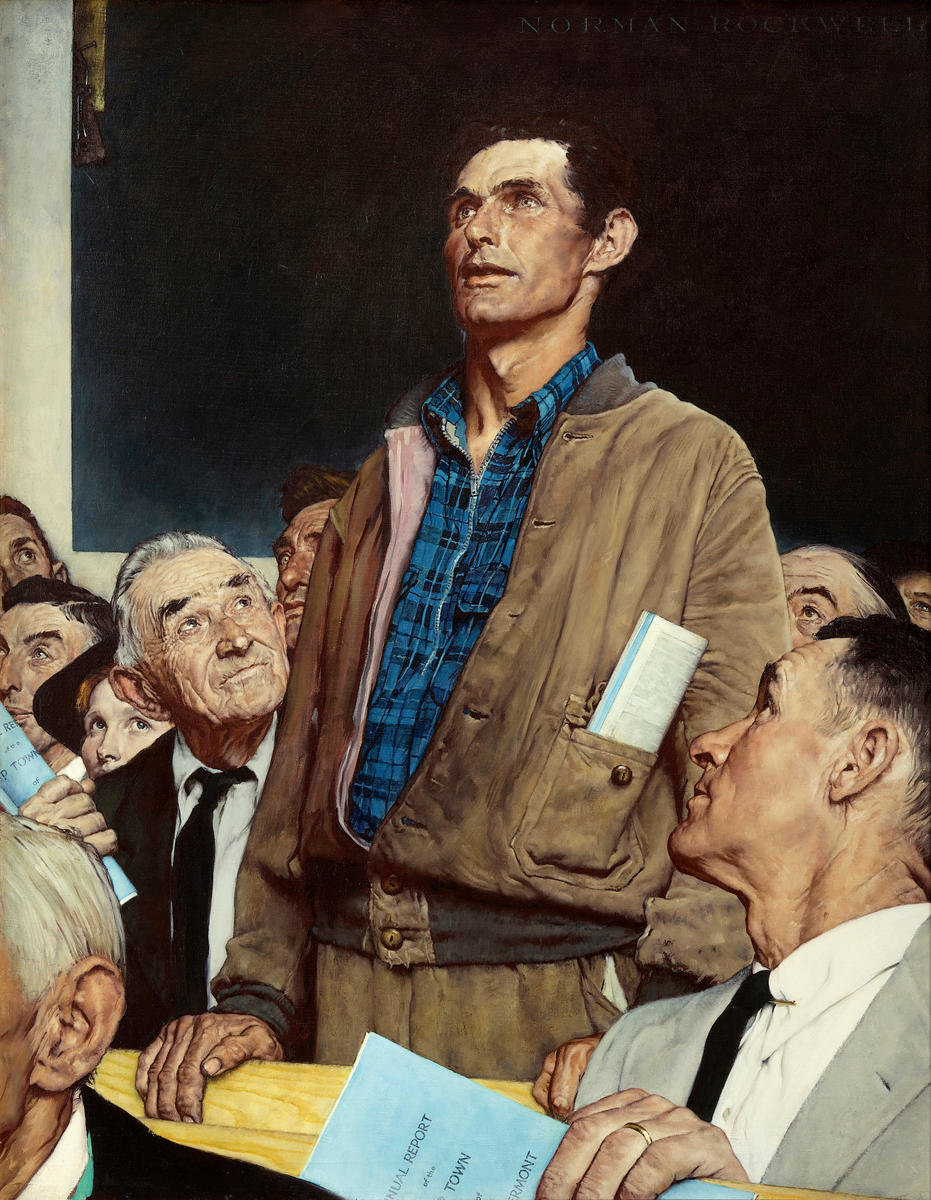

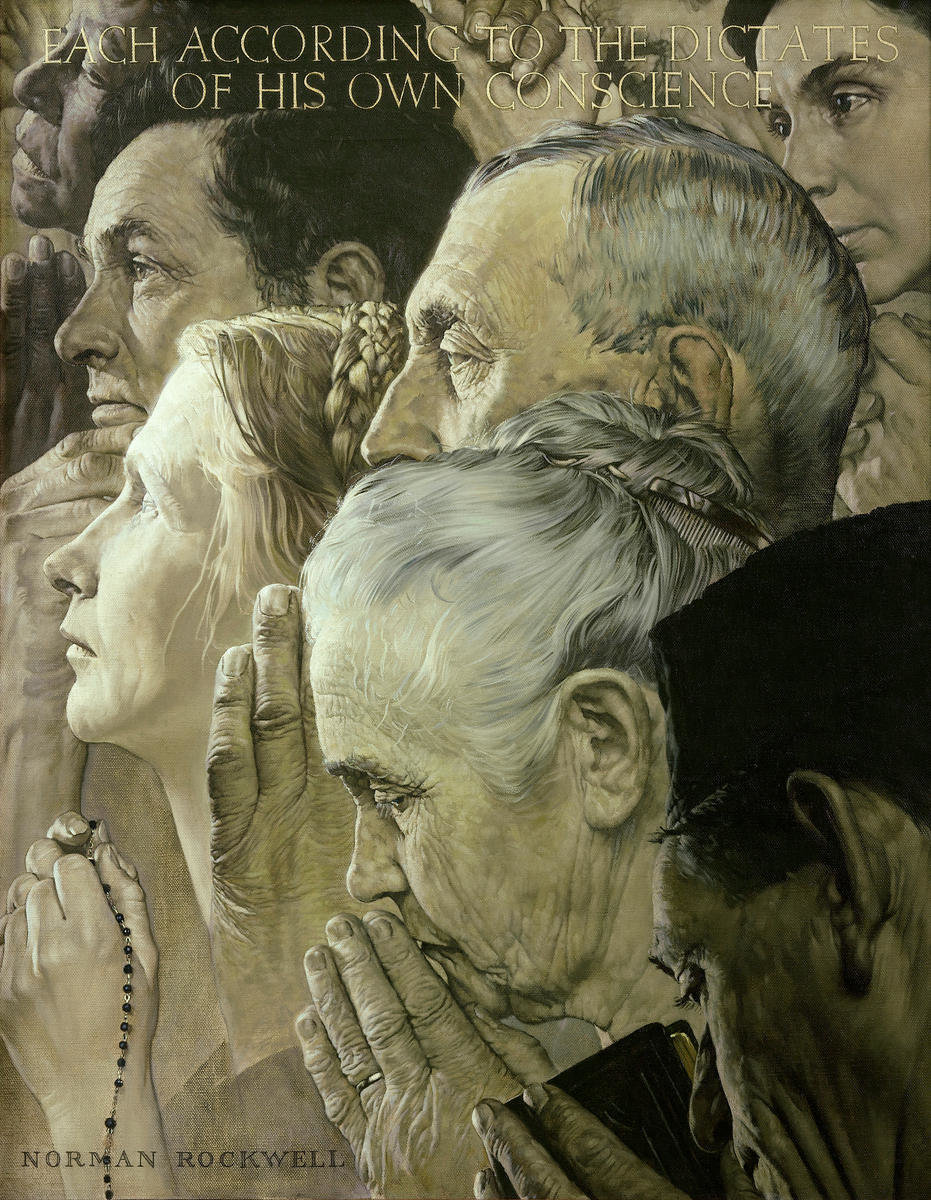

Some of his most remarkable works from this era are the Four Freedoms, a four-painting series he created in 1943, inspired by Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s 1941 “Four Freedoms” speech to Congress. In early 1941, with America’s early involvement in the war, Roosevelt needed to make clear that the values and liberties Americans took for granted were under attack. In particular, Roosevelt emphasized the four essential freedoms: freedom of speech and expression, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. Through the Four Freedoms, Rockwell translated these political ideals into relatable scenes of American life that resonated deeply to a nation at war.

The Four Freedoms became the face of a massive war bond campaign that toured sixteen cities, raising $133 million for the war effort. Citizens who bought war bonds received full color reproductions of the paintings, making them common symbols of American patriotism. These images were patriotic promotions of what America believed it was fighting to preserve: wholesome family dinners, peaceful worship, respectful civic debate, and safe homes for children.

Yet even within these quintessentially patriotic paintings, something more progressive was quietly at play. Despite being widely viewed as conservative due to his “wholesome” subject matters and traditional art style that contrasted the rise of abstract expressionism in the 1940s, Rockwell actually held progressive political views. Freedom of Speech was based on a 1942 town meeting that Rockwell attended where Jim Edgerton stood up in questioning the financial implications of a school construction project, concerned about the taxes on his struggling farm. What made this painting radical was not just the act of disagreement, it was who was doing it. The speaker was dressed as a working class man in casual clothing with visibly worn hands, contrasting sharply with the well dressed professionals surrounding him. Rockwell's choice to center ordinary working Americans as his subjects visualized democracy not as debate among the educated elite, but as a blue collar farmer challenging those “above” him and being heard.

Freedom of Worship and Freedom from Want also pushed against the constraints of the time. Freedom of Worship featured multiple ethnicities and religions, with people of different faiths shown in moments of prayer. The work included Black worshipers positioned on the edges alongside an identifiable Jewish man on the bottom right, a Protestant woman in the bottom center, and a Catholic woman holding a rosary on the bottom left. The appearance of Black Americans in Rockwell's painting signaled the artist's own openness to social change. Even Freedom from Want, the most seemingly apolitical of the series, subtly represented Rockwell’s progressiveness. The people shown weren't all blood relatives but rather included friends and neighbors sharing a meal together. This portrayed the idea that families can be formed through choice and meaningful relationships rather than just biology.

However, for all the subtle radicalism of the Four Freedoms, they still depicted an overall White America. This is because The Saturday Evening Post had strict policies that reinforced racial prejudices of its predominantly White, middle class readers. The main one enforced that Black Americans could be depicted only in service industry roles, never as equals to White Americans. The gap between Rockwell’s personal beliefs and these editorial constraints created a large tension. While his paintings were subtly inclusive, like a Black face in a crowd of worshipers, the overwhelming whiteness of his works reflected the magazine’s limitations more than his own vision of the American Dream.

By the early 1960s, that tension had reached a breaking point. The Civil Rights Movement was reshaping American discourse and consciousness, and Rockwell could no longer continue just subtly representing his beliefs. After 47 years and 322 covers, Rockwell left The Saturday Evening Post in 1963, a remarkable act of courage. After all, he was walking away from the platform that made him famous and gave him financial stability for years.

What came next was the second part of Rockwell’s career. He joined Look magazine in 1964, a magazine more willing to engage in controversial social issues. In 1964, he painted The Problem We All Live With, depicting six year old Ruby Bridges being escorted to school by federal marshals in 1960. Ruby, dressed in a dainty white dress and carrying her school supplies, walks past a wall that has a racial slur and a splattered tomato across it. Rockwell crops the composition before reaching the marshals’ faces, emphasizing their protective presence but Ruby’s isolation in that moment; she is left all alone in her courage. The contrast to his earlier work is very evident. While the Four Freedoms depicted America’s ideals, The Problem We All Live With depicted America failing to live up to her ideals and a child forced to be braver than the adults around her.

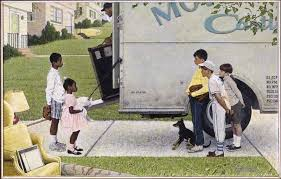

Rockwell continued his engagement with the Civil Rights Movement in other works for Look magazine. Murder in Mississippi (1965) depicted the murders of civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner who were killed by the Ku Klux Klan in 1964. New Kids in the Neighborhood (1967) showed a Black family moving into a White neighborhood, showing the shared curiosity between Black and White children cautiously meeting for the first time, a moment signaling the beginnings of racial integration.

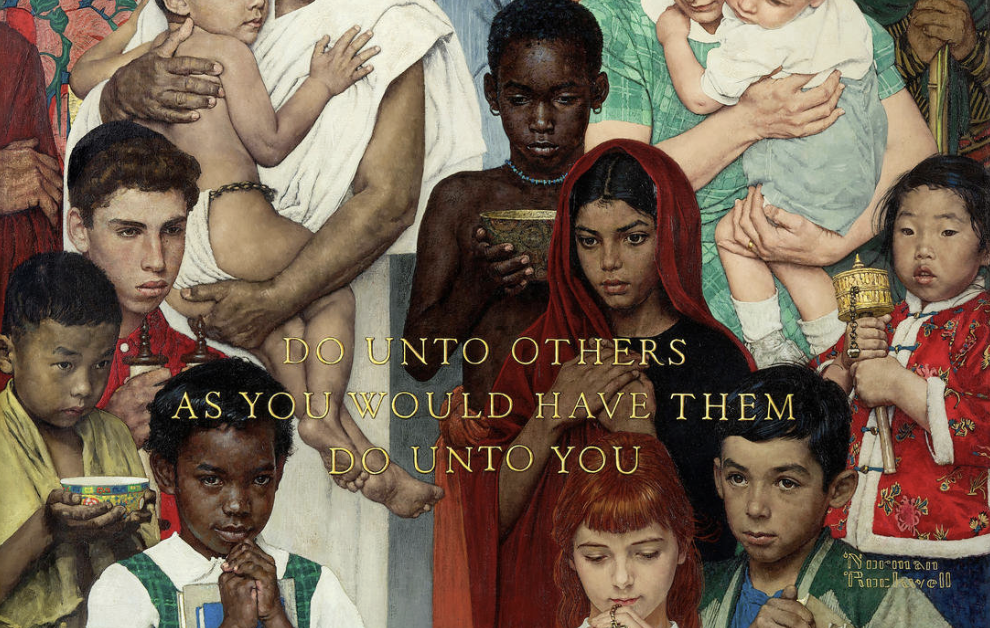

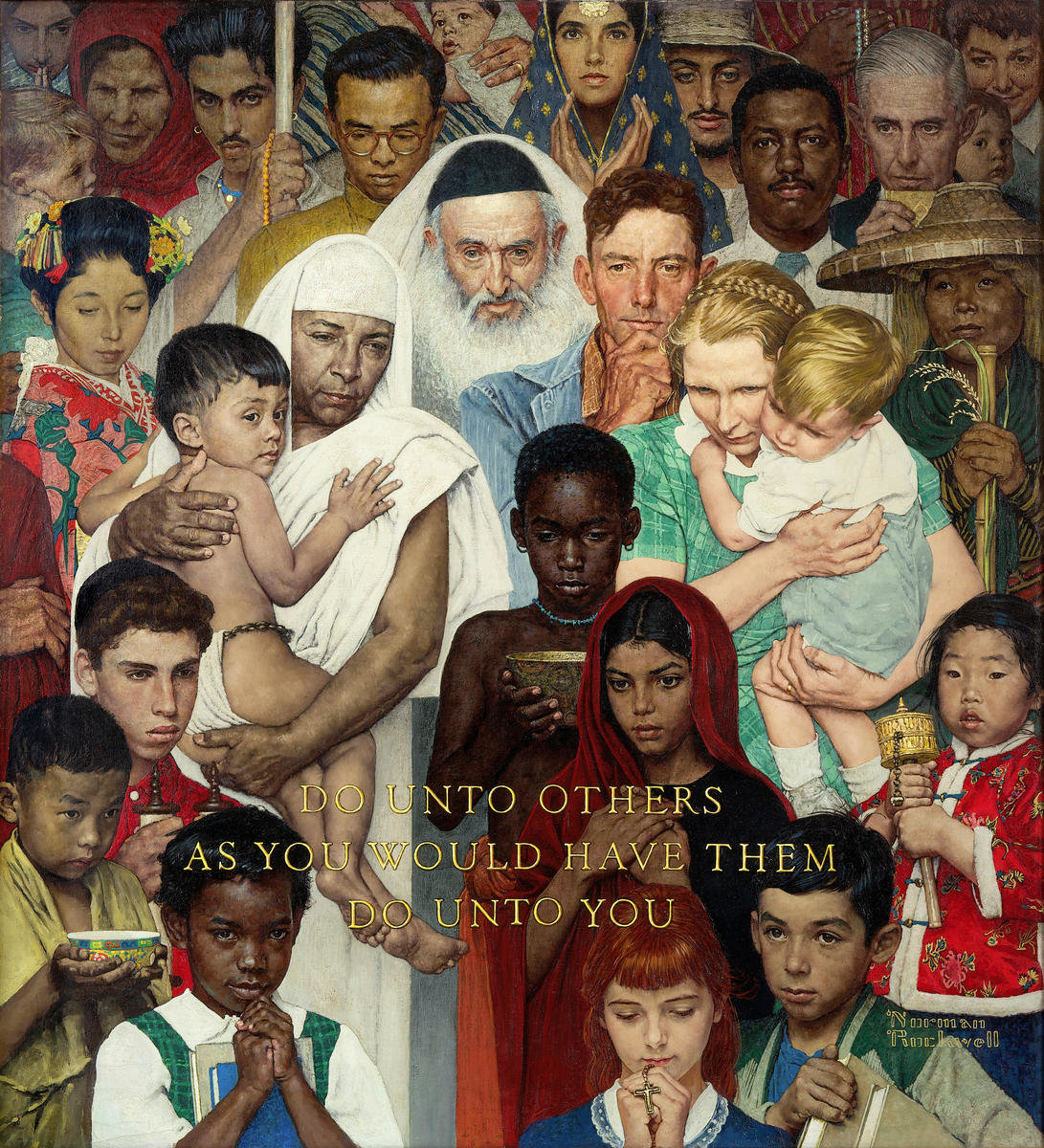

Despite the large differences throughout Rockwell’s artistic trajectory, they leave a legacy that comes to show something very profound: that both phases of his career, the idealistic and the critical, represented different sides to the same American story. Rockwell didn't abandon the American Dream in his later years; he redefined it to become an active pursuit of justice. The Golden Rule encaptures Rockwell’s lasting image of the American Dream. With a similar composition to Freedom of Worship, the Golden Rule depicts people of all ethnicities, ages, races, and religions. Rockwell proudly scatters people of all such characteristics across the painting, not centralizing White Americans and marginalizing those different like he had to do while at the Saturday Evening Post. At the forefront, a block of golden text reads, “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” This statement preaches a very self-aware and conscious way to think, a mindset that America needed and still needs to take on.

Rockwell’s legacy is not just as the painter of the American Dream but as the painter of the American conscience. In both roles, American idealist and social critic, he held up a mirror to the nation: first to show Americans who they wanted to be, with subtle progressive hints of who they might become, and then to show them who they needed to be.

(Cover Image: The Golden Rule, Norman Rockwell Museum via Prints.nrm)