Analyzing how the techniques used in the earliest cave paintings reveal insights into human creative development and form the foundation for later artistic expression.

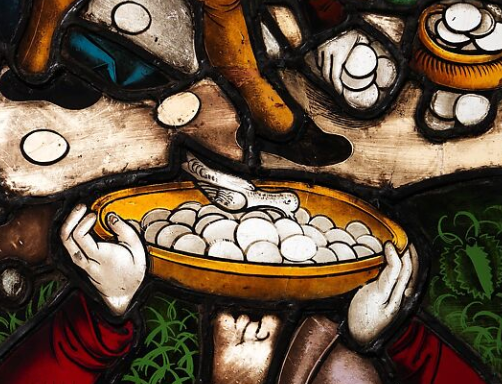

Striving for the divine. This is something Christianity has always centered around, a desire for closeness to God. One particular, essential way of doing this is by consuming the Eucharist, a Catholic tradition with deep scriptural roots. Taking the Eucharist is a central part of the Catholic Mass, where one consumes the body, blood, soul, and divinity of Jesus Christ, present in unleavened bread after a priest has blessed it. This practice ties into the words said by Jesus, “I am the living bread that has come down from heaven,” and it also connects to Jesus’s incarnation, when he was brought to the earth by God to both become man and engage with men. It wasn’t until the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 that the word transubstantiation was agreed upon as the correct expression of Eucharistic doctrine; thus, meaning that Eucharistic bread can contain the real presence of Christ through a priest's prayers. And following the approval of transubstantiation, the Mass began to center around the Host, especially in the later fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. This shift affected the construction of and imagery present in churches and cathedrals. One such cathedral that featured iconography around the Host was Salvatorkirche in Germany. The stained glass panel, Gathering Manna, depicts a scene from the Old Testament (before Christ had come to earth) showing men collecting manna, a type of spiritual food provided by God, that looks like pieces of the Eucharist. Gathering Manna expresses a central obsession with the Eucharist and the timelessness that the Host represents in connection to God’s never-ending presence on earth.

This work is thought to have been created by Friedrich Brunner and his workshop between 1497 and 1499 based on the compositions of Jan Pollack. The panel was originally located in the Salvatorkirche church in Germany, but was later removed in 1906. The work is nineteen and three-quarters by twenty and seven-eighths inches in size. Gathering Manna presents a scene from the Book of Exodus, depicting Moses (front left) and his brother Aaron (back left) instructing the Israelites as they collect manna.

To begin looking at the artwork, it is important to consider the medium and how the presence of light through this colorful window would have conveyed a positive view of the manna and, by extension, expressed divinity in the Eucharist. Stained glass techniques changed greatly throughout medieval times, and towards the end of the 1400s, there was more emphasis placed on a “painterly” style. Additionally, new techniques allowed cleaner shifts between colors and a brighter, gem-like effect. These techniques seem to be prominent in this stained glass work, as the colors are quite vibrant, and there are clear separations between color blocks; even the white manna has been separated from the slightly darker beige ground behind it. This vibrance heightens the spiritual importance in the story being depicted. Furthermore, there is a gem-like quality emphasized, especially in the hat of Aaron (top left), its red gem encircled by gold braiding bowing towards the manna. This seems to imply a sense of respect for the food that is given by God, as even the most beautiful, earthly things succumb to God and his gifts. Then, considering that light would have shone through this glass is quite important. There was the idea that the light coming through these windows was divine, and the liturgical commentator Sicard of Cremona “Compares the windows to the five senses, which facilitate the understanding of the Holy Word” (Martina Bagnoli, Treasures of Heaven: Saints, Relics and Devotion in Medieval Europe, 99). A sensorial and tangible connection to God could be inspired by these windows. Light is a crucial component of a work such as this, as it allows the true colors and details to be expressed. Crafting this stained glass panel would inherently call for collaboration between the artist and natural forces (like light) that were believed to have been from God. And because the manna is white (the lightest part of the panel), it would allow the most light to pass through, making it the brightest part of the piece. Viewers would be drawn to it, seeing what looked like pieces of Eucharist radiating light. Hence, through the light, the presence of God is evoked in the manna and in a broader sense also in the Host.

The dove is another prominent symbol that communicates God’s presence and his intercession in allowing availability of spiritual food. The dove sits on top of the platter of the manna, towards which all of the men look —although it is quite small, its location and many small black details in the wings and head make it stand out against the pure white pieces of manna. It also seems to be bowing down, again insinuating humility in the face of God’s goodness in providing spiritual food. In early Christian art, doves symbolized the Holy Spirit in scenes associated with Jesus’s birth, baptism, and death, and indicated the presence of the divine throughout the Old and New Testaments—a visual tradition Gathering Manna continues. The dove insinuates that God is truly present. Furthermore, the dove references transubstantiation. The manna or bread is being touched by the Holy Spirit, and subsequently the power of God, and in transubstantiation, the bread is turned, through the power of God (mediated through a priest), into the true presence of Jesus. As scholar Charles Zika says, the “Host’s broad appeal [was] versatility and power”. It is interesting to consider the idea of versatility in this depiction of the Host in this Old Testament scene through the dove; there is an effort to show the Eucharist even in older subject matter via the versatile symbolism of the dove. In Gathering Manna, the presence of the dove pushes this idea that God’s provisional powers have remained throughout time and, just as he gave the Israelites manna, he continues to give even more through the Host (and his son's apparent presence in the Host).

This presence of God is also insinuated by the characteristics of the four men in Gathering Manna who guide the viewer towards God's goodness in his gift of divine nourishment. The Israelite located in the bottom right corner holds up the golden plate that contains the manna and the dove. His arms are bent at acute angles, signifying the weight of what he is carrying. Despite this burden, however, he has a contented expression with a slight smile on his lips. This signifies the idea that, even though following God may be a difficult and hefty task, it is also a joyful one. Above him, another Israelite with a similarly content expression is gathering an abundance of manna to put in the dish. His gaze is downward towards all of the manna, and his body is bent over, again seemingly bowing down to the presence and power of God. Aaron, located at the top left corner, is also bowing down to the dish of manna, and his face is concealed due to his position, suggesting that human features are meaningless without God. There is a deep faithfulness expressed in these three mens’ positioning. A guiding idea of Catholic beliefs is, “A potential for transformation…of the Eucharist taking on flesh and blood within the faithful”. An understanding and relationship with God allows knowledge of the true benefits of the Host. Therefore, viewers who were to see the deep faith of these Old Testament figures, who never knew of Jesus Christ, would have been directed to have similar devotion towards the Eucharist. And finally, Moses is at the bottom left corner pointing toward the dish of manna, seemingly directing the work. Interestingly, he is the only one with a fully visible face and eyes. This may be due to the fact that he is acting, at this point in the Bible, as a mediator of God’s word. He is therefore potentially the only one that fully understands God’s power at this time and can see the miracle most truthfully. This connects to the priests’ role in transubstantiation, as mediators of God’s power, delivering the prayer that turns the bread into the true presence of Jesus Christ. Therefore, this position of Moses in relation to the manna draws parallels to that of a priest with the Eucharist. These positionings further the idea that God has continually made himself available on earth to provide humanity with meaningful and pertinent sustenance.

In conclusion, Brunner’s work, Gathering Manna, displays how New Testament themes, such as the Eucharist, were compiled with Old Testament stories in a fascination with expressing God’s timeless presence. Through the usage of stained glass, there is an apparent emphasis on light, and particularly the light coming through the brightest point in the work, which is the manna. Because this manna looks so similar to the Eucharist, the light shining through would direct viewers to contemplate the Host. Additionally, the depiction of the dove on top of the manna is a signifier of the Holy Spirit. This insinuates God’s true presence in the manna, just as he is present through Jesus in the Eucharist. Finally, the positions and features of the four men guide the viewers attention toward the manna, showing reverence and joy in faith, hence directing viewers to have the same regards toward the Eucharist. All in all, the obsession for the Eucharist as the new center of liturgy following the Fourth Lateran Council gives this Old Testament scene direction toward symbolizing this crucial divine sustenance.

(Cover Image: Friedrich Brunner, Gathering Manna, 1497-99, pot-metal glass, vitreous paint, and silver stain, 19 ¾ by 20 ⅞ inches, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, New York, United States of America. Via the Metropolitan Museum of Art)