Analyzing how the techniques used in the earliest cave paintings reveal insights into human creative development and form the foundation for later artistic expression.

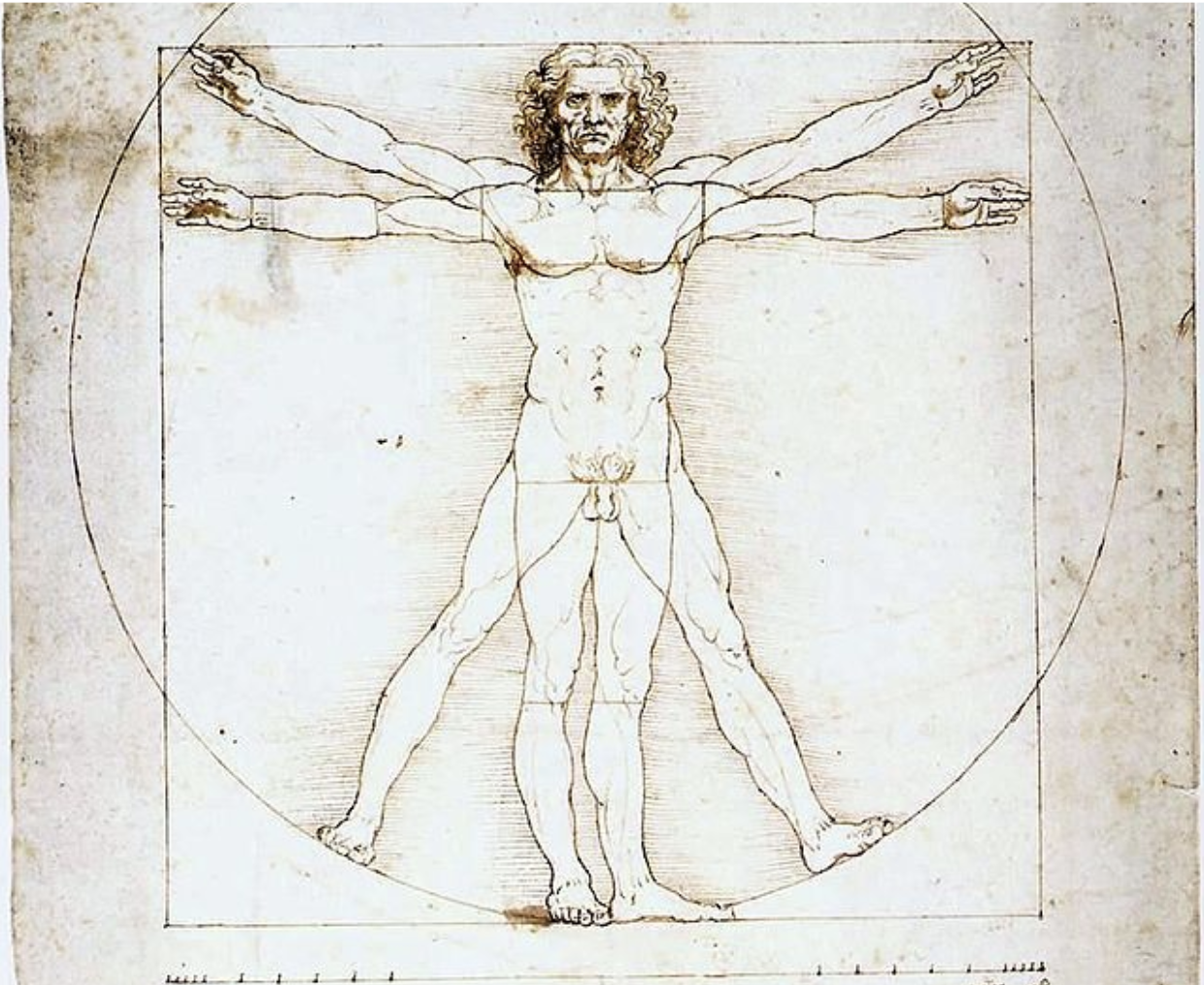

The portrayals of the human figure in Medieval and Renaissance art differ dramatically not only in style, but also in attitude toward the human form itself. After the devastation of the Black Death and a growing disillusionment with purely religious explanations of the world, there was a renewed interest in secular thought and classical texts. It was during the Renaissance era of rediscovery and revolution that the human body began to be portrayed in its more natural or even idealized form to capture the subtleties, beauty, and complexity of the human figure with a depth that had been largely absent during the Medieval period.

This shift didn’t happen without resistance, though. According to Doctor Sanjib Kumar Ghosh, legal and social challenges from strict Christian influence surrounding human dissection presented significant barriers, leading medieval artists to view the nude body at a distance and as an impurity. The dominant anatomical model for over a thousand years was Galen’s, a Greek physician whose work was based primarily on animal dissection. As a result, anatomical knowledge was severely limited, one of many key reasons for the prevalence of distorted figures in Medieval artwork.

At the turn of the Renaissance, artists became key figures in advancing anatomical knowledge, using both science and observation to refine their craft and discover the inner workings of the human body; Leonardo da Vinci, for example, studied the human body at a level of detail few had dared to before. He gained anatomical insights that advanced both medical understanding and artistic development. Michelangelo, another important figure of the Renaissance, also spent extensive time studying the human form through dissection. Though less known for his scientific studies than da Vinci, his mastery of the human form transformed how it was portrayed on canvas and in sculpture.

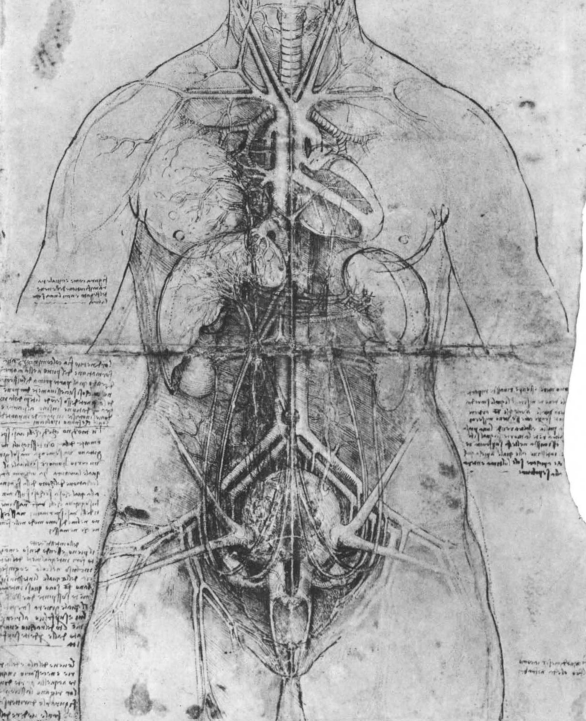

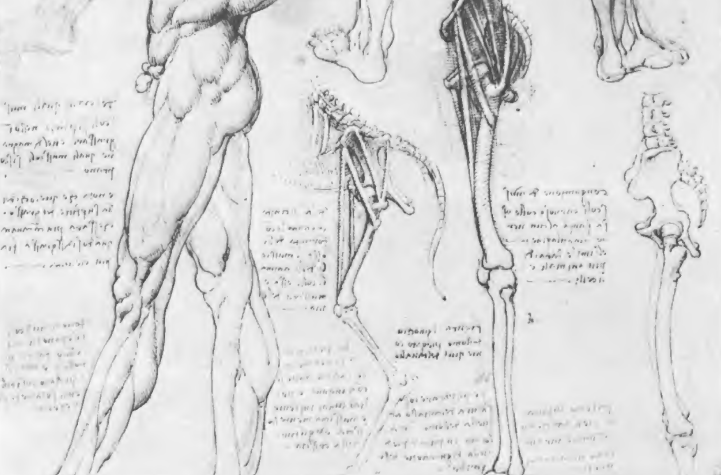

Leonardo da Vinci's anatomical illustrations are among the most renowned studies of the human form from the Renaissance. Over the course of his lifetime, da Vinci produced more than 1,550 sketches of his dissections, which he intended to publish.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, da Vinci extended his investigations to include individual organs and their functions, along with the reproductive, nervous, and circulatory systems. His studies encompassed a wide range of ages and body types, demonstrating a comprehensive approach to human form and function.

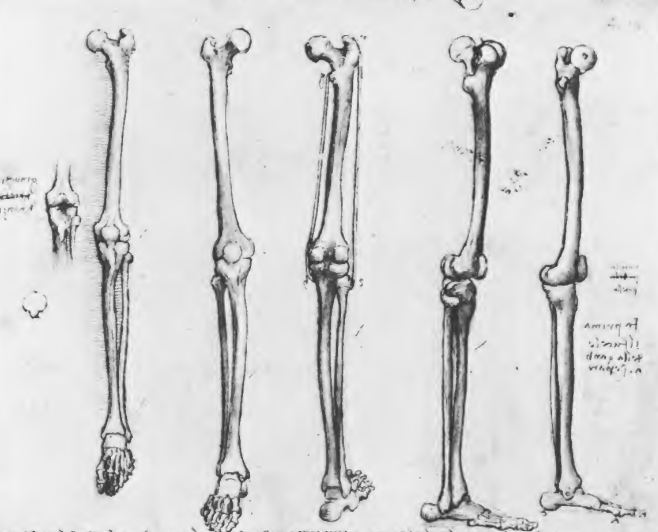

Careful analysis of da Vinci’s work shows that his studies had two primary goals: to understand the human body at a deeper, more nuanced anatomical and functional level, and to render the larger skeletal and muscular forms into comprehensive lessons on anatomy and proportion in his paintings.

According to doctors Wolach and O Wolach, the use of facial expressions in art was a relatively new development during the Renaissance. In contrast to the Middle Ages, which often lacked visible emotion or a sense of soul, da Vinci believed a key component of artistic realism was utilizing expression as a means of conveying psychological depth and emotional complexity. His most notable example, the Mona Lisa, displays a coy, elusive smile that shifts in tone depending on the viewer’s angle, creating a dynamic interaction between art and viewer.

Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical studies were not only groundbreaking in content but also in technique. One of the most essential elements of his approach was the use of chiaroscuro (the manipulation of light and shadow) to depict form and depth with clarity. This technique allowed him to render anatomical structures with a three-dimensional quality, enhancing both the scientific accuracy and visual readability of his illustrations.

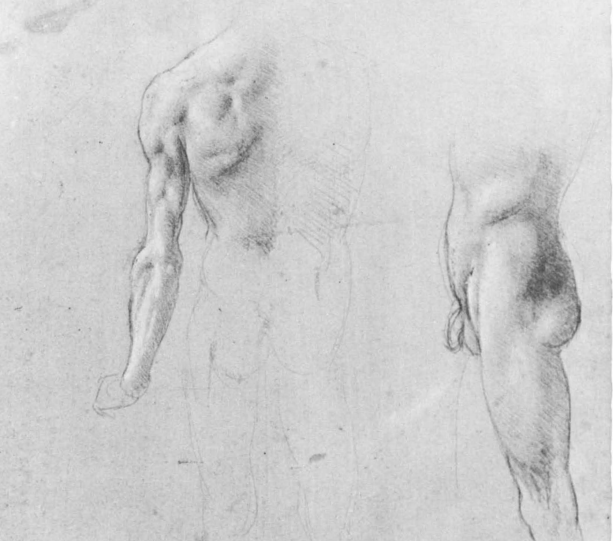

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s digital collection of da Vinci's case studies combines the remaining pieces of his studies into a single body of work. For example, in case study 47, titled Muscles of the Arms and Legs, da Vinci used chiaroscuro to suggest the depth and curvature of musculature without relying heavily on outline or boundary sketching. This technique was used again in study 2, which focused on capturing a dissection of the internal organs. da Vinci used precisely placed highlights and shadows to differentiate the veins and arteries from the larger organs.

In his sketch Two Views of the Skull (as seen below), da Vinci depicts the three-dimensional form of the human skull as seen through dissection. He captures it with a naturalism that stands in stark contrast to the stylized, often elongated, oval-shaped skulls of Medieval art. His piece is realistically proportioned, and this is translated into his finished works.

Drawing 26B demonstrates another application of perspective: this time, analyzing the structure of leg bones in various positions. These studies were instrumental in helping da Vinci accurately render the human form in a range of dynamic poses.

One of the most fascinating aspects of da Vinci’s work is his comparative anatomy studies, in which he dissected animals and humans to compare their frameworks. Case study 42 examines the leg bones of a human and a horse, and stands out as an early investigation into the structural similarities across species, offering insight into the idea of shared skeletal features and common ancestry.

At the same time, renowned Renaissance master Michelangelo, celebrated for his stunning paintings and magnificent sculptures, also studied from life and engaged in dissection. According to Dr. Garabed Eknoyan, Michelangelo had already performed public dissections by the age of eighteen and regularly studied live models. Although few of his anatomical drawings have survived, the existing fragments suggest that Michelangelo’s primary aim was to depict a well-proportioned and anatomically accurate human body in all positions and forms in his finished artworks. Because of this, his focus centered largely on the muscular and skeletal systems, particularly how muscles function in various poses.

Michelangelo’s anatomical studies directly informed the striking realism of his masterpieces, with David standing as a prime example. As noted by professor and researcher Paola Soldani, even the superficial veins on the hands and forearms are rendered with remarkable accuracy. This level of precision suggests not only close observation from life, but likely also firsthand knowledge gained through dissection. Whether drawn from live models or anatomical study, such subtle detail reflects a profound understanding of the human form and contributes to the work’s overall mastery of the human body.

Michelangelo’s statue of Moses is probably the most impressive demonstration of his command over the subtle complexities of the human body. While the eight-foot sculpture is striking in scale and presence, it’s the small detail of the raised pinky finger on the figure’s right hand that truly marks it as a testament to anatomical precision. The finger is lifted just slightly, causing a specific forearm muscle to flex in shadow. This muscle only becomes visible in this exact position and is notoriously difficult to observe, even when drawing from life. This minute yet deliberate feature reflects a profound understanding of human anatomy, likely gained through dissection of muscle.

Anatomical illustration plays a vital role in enhancing visual learning and comprehension of complex biological systems. Both Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo used illustration as a way to better understand human anatomy based on their direct observation and dissection. Their drawings offered a level of clarity and depth that transformed anatomy from abstract knowledge into something tangible, essential for both modern medical education and the attitude towards the human body.

Additionally, the aggressive shift toward deep admiration for the human body and its power caused striking differences in Renaissance artistic style compared to the Medieval period. Thanks to da Vinci and Michelangelo’s groundbreaking dissections and precise studies of musculature, bone structure, and proportion, the human body was redefined as a subject of artistic reverence and beauty. The public no longer viewed the human form as something to obscure due to Christian notions of impurity, but as a topic worthy of rigorous study and celebration. Humans could be captured in their idealized forms to exemplify the potential of the human body and its musculature. Their work opened the door for people to appreciate the human form and to feel a sense of pride in what it represented, while also reinforcing the idea that admiring the body was not sinful or impure but could instead be understood as honoring God’s intricate creation.

(Cover Image: Leonardo da Vinci, Vitruvian Man, via File:Leonardo da Vinci- Vitruvian Man.JPG - Wikimedia Commons)