Analyzing how the techniques used in the earliest cave paintings reveal insights into human creative development and form the foundation for later artistic expression.

The Church Fathers on Unrighteous Drunkenness

In the fifth homily of his Baptismal Instructions, the fourth-century Doctor of the Church St. John Chrysostom exhorts catechumens to the Christian faith to not only “turn aside from drinking to excess, but also to avoid the drunkenness which comes without drinking wine[,]...[f]or this kind is far more dangerous.” In other words, Chrysostom contends that the emotive afflictions which guide the human soul to perdition, namely “vainglory, haughty madness, and all [our] deadly passions,” produce a far more spiritually detrimental effect on a believer’s power of discernment than wine, as such maladies corrupt a rational mind into a font of mayhem and disorder. Indeed, this idea of drunkenness as a spiritual condition rather than solely physical intoxication is not unique to Chrysostom's writings. For, in the homily itself, Chrysostom bases his judgment on the testimonies of the Prophets and St. Paul, with the latter arguing in his Letter to the Ephesians to abstain from all forms of drunkenness in order to (according to Chrysostom's exegesis) circumvent the necessary “destr[uction] [of] the treasure of virtue” that it precipitates. Consequently, Chrysostom decries drunkenness as a “self-chosen demon” that fans the flames of corporeal passion and renders Wisdom mute. This perspective regarding the rational and spiritual deterioration inherent in lecherous drunkenness was the general consensus among the Fathers, for St. Ambrose also pronounces that “there would be no slavery, were there no drunkards’”; he here references both the idea of spiritual slavery to the sin of drunkenness (due to the frequency of its satiation) and the physical punishment of Ham’s descendants in the story of Noah and His Sons, according to St. Thomas Aquinas in Question 150 of the Second Part of the Second Part of his Summa Theologiae.

The Church Fathers on Righteous Drunkenness

However, when taken from the opposite perspective, spiritual drunkenness with the Blood of Christ, the Sacrificial Lamb, was seen as an admirable virtue among the Church Fathers. For instance, St. Isaac the Syrian, who often stresses the necessity of holy inebriation in his ascetic homilies, lauds the man who, in contemplative prayer, reaches the state at which “‘he remains continually in amazement at God's work of creation–like people who are crazed with wine, for this is ‘the wine which causes the person's heart to rejoice,’’” as Bp. Hilarion Alfeyev cites in his book, The Spiritual World of Isaac the Syrian. St. Augustine shares this viewpoint, arguing that believers should seek to intoxicate themselves with the Holy Spirit in their ecstatic singing and praise of the Lord of Hosts, for the “‘Spirit of God is both drink and light,’” as Raniero Cantalamessa O.F.M. Cap. quotes in his book, Sober Intoxication of the Spirit: Filled with the Fullness of God. In this vein, the Cambridge Companion to Augustine's Sermons specifically highlights how Augustine viewed the Pentecost of the Spirit as not an overturning of the Pentecost of the Law but rather as the palpable “drunkenness from the ‘intoxicating and splendid chalice’” of Christian charity toward God and neighbor, modeled by the example of the early martyrs. Augustine's sermon thus offers a tenable reason for the crowd's misconception that the Apostles were drunk after their reception of the Holy Spirit in the Book of Acts; the Sons of the World mistook the Sons of Light for worldly drunkards from wine instead of saintly partakers in the Blood of the Lamb. This explanation is further vindicated by virtue of the fact that the Pharisees denounced Jesus as a glutton and a drunkard in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, when in fact he epitomized the divine ideal of the drunkenness from charity in his embrace of tax collectors and sinners. In his memory, Catholics emulate Christ’s joyful, unifying feast in the Eucharistic Celebration at Mass, consuming his sacred Body and imbibing his veracious Blood to revitalize our souls.

Drunkenness in Scripture

Although scripture abounds with such justifications for these arguments in its resplendent parables, stories, and accounts from the time of the creation of the world to the beginning of the early Christian Church, perhaps the deleterious effects of what St. Clement of Alexandria calls “the Bacchic fuel of the threatened danger [of unchastity]” (in his treatise, “On Drinking”) abound most plainly in the Book of Genesis account of Noah and His Sons. In this story, Noah, the patriarch of the family, fails in his obligations to his kin by his abuse of alcohol to the point of severe impairment, thus fulfilling the former form of wretched drunkenness (viz., that from wine). Likewise, it is of note that, his wicked son, Ham, who takes advantage of his derelict father, also is drunk, albeit on the latter form (viz., that from the passions). Ham clearly suffers from the “haughty madness” that Chrysostom describes in the aforementioned homily, since he “saw the nakedness of his father,” which scholars typically deduce could either mean that he castrated Noah, raped him, voyeuristically gawked at his father's foolishness, or, as Bergsma and Hahn argue in their treatise, “Noah’s Nakedness and the Curse of Canaan (Genesis 9:20-27),” raped his mother; in any event, he allowed his pride to consume him to the point of dishonoring his father. As a result, Ham’s son, Canaan, was cursed to be a servant of the descendants of his two brothers, Shem and Japheth, who righteously covered the nakedness of their father. Bergsma and Hahn thus conclude that Canaan was punished instead of Ham because he was the illegitimate issue of the incestuous union between Ham and his mother, even though Ham himself committed the act and deserved Noah’s curse. With this explanation in mind, it would seem apparent that the story of Noah and His Sons only archetypically models the most vile form of unrighteous drunkenness from wine and the passions.

The Morality of Noah's Drunkenness and its Early Modern Depictions

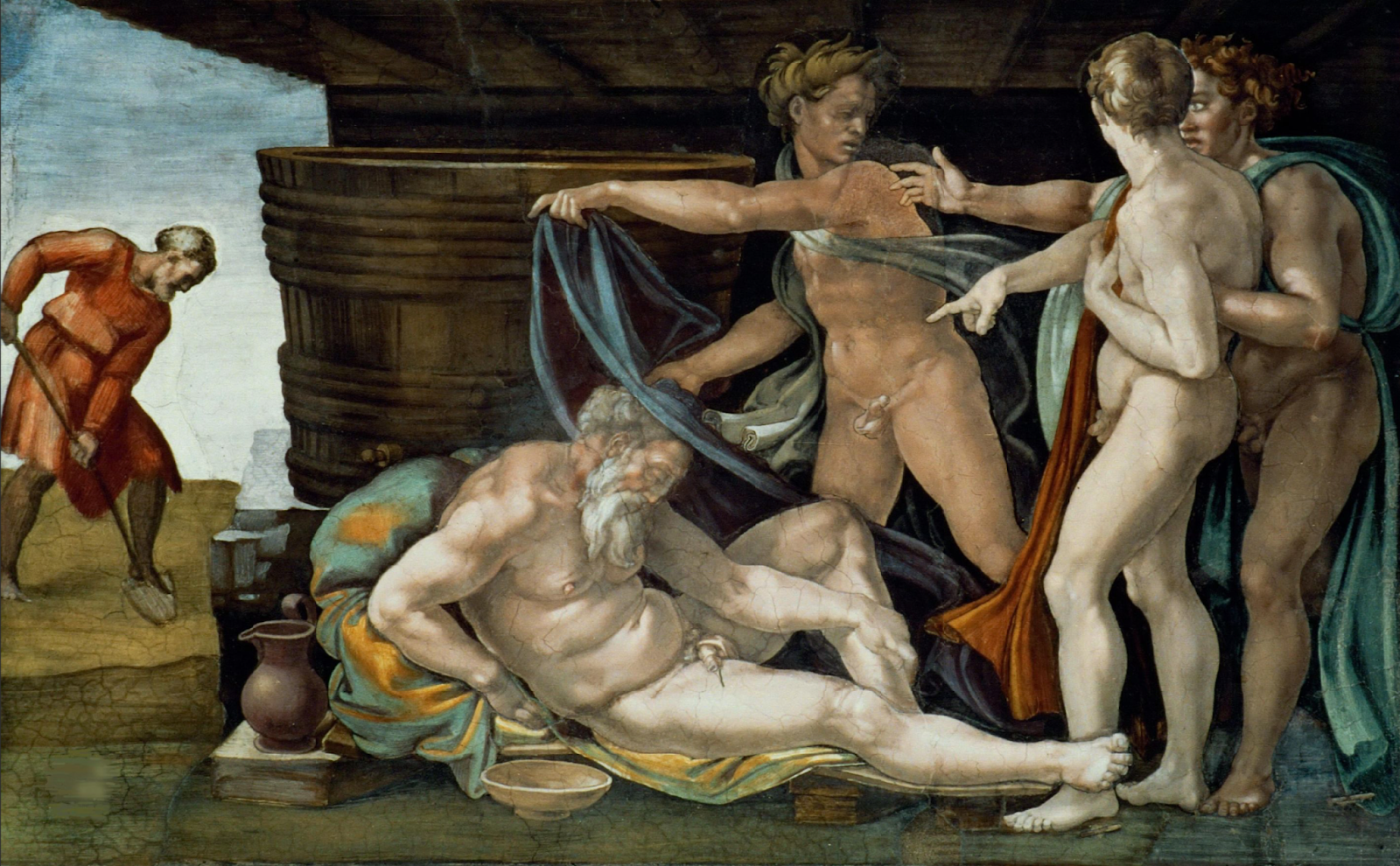

On the contrary, St. John Chrysostom argues in his homily on the subject that Noah's drunkenness did not constitute sin, for he was the first to ever drink the fruit of the vine and thus did not know its alcoholic effects; through this exoneration, Noah became a prefigurement of Christ, since, according to Edgar Wind in his book, The Religious Symbolism of Michelangelo: The Sistine Ceiling, Noah's drunkenness came to prophetically symbolize “‘Christ drunk with his passion’, [...] [with his wine as] a token of the ‘sacrament of the chalice’ [...] and [his] derision [...] anticipat[ing] that of Christ.” Michelangelo's depiction of this same subject on the Sistine Chapel ceiling also points toward this interpretation, according to Professor Itay Sapir (a Ph.D. in Art History and Aesthetics) in his "Convergences and Divergences" commentary on the Sistine Chapel fresco of The Drunkenness of Noah. He cites Michelangelo's purposeful inclusion of surrounding motifs, such as the Delphic Sybil and the Prophet Joel, who were respectively associated with “derision and the crown of thorns, and with wine and drunkards,” to illustrate how he intended for this scene (which was rarely depicted) to serve a theological and emblematic purpose in the composition of the ceiling. While Dr. Sapir highlights that Michelangelo faces Ham away from the viewer in order to make him less accessible and racially distant, I would argue that Ham's anonymity adds to the experientiality of the scene, since, in so doing, Michelangelo implores the viewer to ponder when they have derided Christ, disobeyed his commandments and Gospel, and exposed their brothers and sisters to detraction or moral judgment.

In a complete reversal of Michelangelo's composition, Andrea Sacchi's 1629 sketch of the same scene points even more potently to the gravity of Ham's sin in comparison to that of his father. In the sketch, Ham stares right at the viewer as he gestures both arms toward his disgraced, entirely naked father; in a way, Sacchi configures the scene so that the viewer themselves is an unwilling viewer of Noah's nakedness, whilst Ham wickedly revels in the sight with a wry smile and haughty glare that boldly jump out of the piece's red chalk lines. The connection between Christ and Noah is made apparent, since Ham possesses a similar demeanor to Pilate, as he gestures in Ecce Homo fashion and possesses a countenance with an air of cynicism and intrigue, particularly matching Pilate’s Johannine disposition. The unbeknownst expressions of Shem and Japheth, who peer off into the distance and gesture toward heaven (which perhaps serves as a symbol of their righteousness and deference to God) thus juxtapose intensely with Noah's near-Bacchic revelry and Ham's insurmountable indignation. While Michelangelo kept Ham anonymous to perhaps prompt the reader to reflect on their iniquity, Sacchi's portrayal appears to serve the Baroque, post-Tridentine instructional purpose of condemning Ham's actions and positioning the viewer in emulation of the righteous sons of Noah.

In turn, both Sacchi and Michelangelo adapt the story of Noah and His Sons visually so as to underscore the unrighteous and righteous drunkenness of the participants. Due to Michelangelo's emphasis on prophetic symbolism, he principally reminds the viewer of Christ's drunkenness from charity and with his Passion, keeping Ham anonymous so as to encourage the viewer to contemplate their own transgressions and derision of Christ. Due to Sacchi's emphasis on the depravity and scrutiny of Ham, he principally reminds the viewer of Shem and Japheth's drunkenness with love of God and neighbor, emboldening the audience to follow their model of holiness.

Conclusion

Consequently, the motif of drunkenness has had a storied symbolic history in the Church, as, when examined from both extremes (viz., unholy and holy inebriation) it has the potential to both sever and restore communion with God, for it is the agent of the inebriation itself that decides the morality of the act. A faithful witness or period of prayer has the ability to enchant toward heaven, while an unfaithful witness or intoxicating drink has the ability to seduce toward hell. It is with the cognizance of this duality in mind that the Fathers employed drunkenness—a vice and a liberator, lecherous and divine—to instruct their congregations toward the attainment of the Kingdom of Heaven on Earth, with their word echoing into the early modern period by the hands of Catholic artists.

(Cover Image: Giovanni Bellini, The Drunkenness of Noah, Oil on Canvas, Musée des Beaux-Arts et d'Archéologie de Besançon, France, ca. 1515 via Wikimedia Commons.)