The many visual elements of Camille Pissarro’s Field and Mill at Osny (located in the RISD Museum) express the conflicts present between humanity and nature during the Industrial Revolution at the end of the nineteenth century.

The Pelican in Her Piety as the Resurrection and the Life

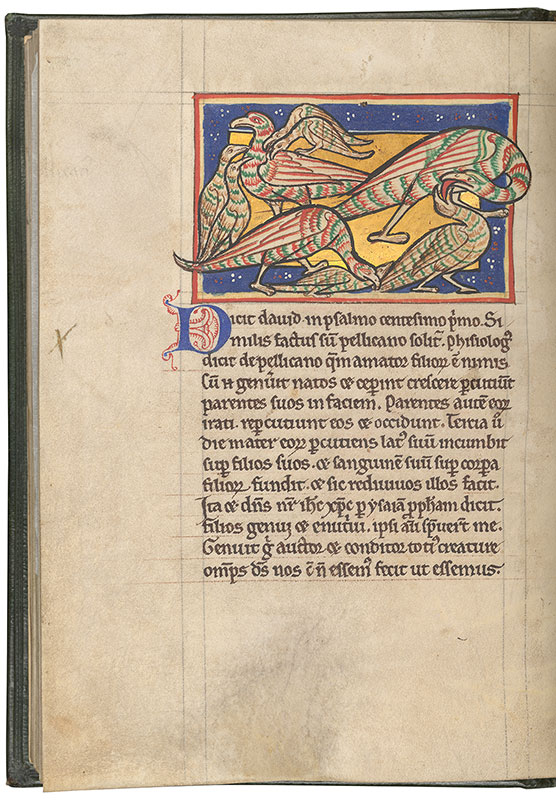

A common motif in medieval manuscripts is the “Pelican in Her Piety,” which depicts a mother pelican piercing her own breast in order to draw blood with which to feed her chicks. Far from an actual natural phenomenon, this allegory originated from a legend that was repurposed by an anonymous second-century Greek author who sought to show the behaviors of nature’s creatures as analogous to those performed during Jesus’ earthly ministry in his Physiologus, according to Remigijus Oželis, an Associate Catechesis Professor, in his article, “Pelican: a Christian Symbol Depicting the Sacrifice of Jesus Christ.” Oželis further contends that, after the work was translated into Latin and promulgated among continental European Christians during the medieval period, the association of Christ with a sacrificial pelican fit into an emergent philosophy which posited that “symbolic meanings [were] the essence of animals” and that such behaviors could be used for Christian moral instruction. In particular, since the Greek author portrays the pelican as having killed her children after they struck her and resurrecting them with her own blood in regret three days later, Christians interpreted this as an allegory for the salvific power of Christ’s blood to revive and redeem the human race, even if we ourselves struck God first with our iniquity, as Rev. Barbara Allen notes in her book, Pelican. In the same vein, the Church Fathers began to adopt the pelican as a visual tool to describe the nature of Christ’s sacrifice. For instance, St. Augustine comments in his “Exposition on Psalm 102” that the pelican’s sacrifice to feed her young, as a hen brooding over her roost, “does closely resemble the flesh of Christ, by whose blood we have been called to life.” He further justifies that the mother’s original slaying of her children matches Christ’s nature by citing Saul's blindness during his Conversion on the Road to Damascus, highlighting this as an instance in which divine affliction prompted a sinner and enemy of the Church to repentance and conversion. In turn, the visual motif of the Pelican in Her Piety originally assumed the significance of the consequences of man’s sin, God’s resultant condemnation of that same sin, and Christ’s power to revive souls from spiritual death, as Ozělis concludes.

Visual Representation of the Pelican as the Resurrection and the Life

It is through this lens that many early medieval manuscripts portrayed the story of the Pelican in Her Piety. Of these, the motif most commonly appeared in bestiaries, which were a genre of medieval manuscript that described the behaviors of earth’s creatures and interpreted them according to the aforementioned symbolic and Christian instructional philosophy. One such notable example is in the MS M.81 fol. 61v manuscript in the collection of the Morgan Library and Museum, in which a dynamic illuminated scene of three pelicans allegorizes the fall and redemption of humanity. In the first section, four pelicans peck at the breast of the mother. According to Augustine’s interpretation, this symbolizes the Fall of Man in Genesis, as the pelicans strike their mother’s breast without provocation. In the next section, it can be seen that one of them has presumably died, while the mother grabs their neck. It is unclear whether the mother pelican killed her own child in retaliation for their initial peck (and thus is strangling them in the subsequent panel) or if she is lifting them up to feed them the blood that she draws from her own breast in the final section. Regardless of the interpretation of the second section, it is apparent that the Christlike mother pelican, who now possesses a countenance more akin to regret or panic than her dignified and stoic expression in the first panel, pierces her own breast as a single stream of blood pours from her beak into the mouth of the slain chick. The miraculous power of Christ’s resurrection of the spiritually dead is made apparent by the immediately erect posture of the pelican, despite the fact that the mother does not support their limp neck and their eyes still remain closed. As a result, this manuscript helps illustrate the trend in the earlier medieval period (as it is estimated to have been created circa 1185) of portraying the Pelican in Her Piety as the agent of both the destruction and rebirth of her fallen chicks, mirroring the duality of the wrathful and merciful triune God, as written in the Book of Habakkuk:

“O Lord, I have heard the report of thee,

and thy work, O Lord, do I fear.

In the midst of the years renew it;

in the midst of the years make it known;

in wrath remember mercy.”

The Pelican in Her Piety Becomes a Divine Physician

However, in spite of this duality, the harsher interpretation of the pelican slaying her own young, which was a rather unappealing image to apply to the God of love and mercy, eventually gave way to alternative formulations in which the chicks were killed by a devilish serpent or threatened by starvation. In this version, the mother virtuously sacrifices herself so that her children might live, as Rev. Allen further notes in Pelican. Thus, in these interpretations, the pelican became less of a regretful executioner (to which one may compare the LORD before the Flood) and more of a blameless victim crushed for the salvation of her children (to which one may compare Christ, the Suffering Servant). In turn, it is far more likely that when composing his devotional prayer Adoro te devote, in which he worships Jesus as the “Pie Pelicane” (Good Pelican) whose single drop of blood could be spilt for the salvation of all sinners, St. Thomas Aquinas viewed the legend in this fashion rather than in the more retributive sense. Ozělis supplements this claim, positing that the assumed theological significance of Christ’s power as a blameless victim to protect souls from death (and not just revive them from death) matched his intention behind the poem, which was to honor the Eucharist, through which Catholics receive spiritual sustenance. It is therefore fitting that the pelican was (and remains) the quintessential representation of the necessity of spilling Christ’s blood for the nourishment of souls and bodies in spite of our fallen nature, for, as St. Paul wrote in his Letter to the Romans, “God shows his love for us in that while we were yet sinners Christ died for us.” Consequently, Christians, in light of this more charitable interpretation of the legend of the virtuous pelican, portrayed Christ as not only the Resurrection and the Life but also the Divine Physician, tending to both the spiritually dead and ailing.

Visual Representation of the Pelican as the Divine Physician

It is through this lens that later medieval and early Renaissance manuscripts more commonly portrayed the motif of the Pelican in Her Piety, based on the chronology portrayed in the preceding paragraph and the general favorability of the later interpretation over the earlier one. An example of the Pelican as a Divine Physician comes from a Book of Hours manuscript (MS M.1004 fol. 157r) made circa 1420 –1425 in the Morgan Library and Museum. The Pelican in Her Piety appears at the top of the page, which contains the text from the mass celebrated on Trinity Sunday, surrounded by minute flora and fauna and other mythological animals in the margins. In the depiction, the Pelican in Her Piety emotively pierces her own breast as blood dramatically sprays into the mouths of her chicks, who are clearly alive and anticipating a meal from their mother; the anonymous artist’s choice to portray the blood as a gush instead of a wave more potently reminds the viewer of Longinus’ piercing of Christ’s side on the cross. Therefore, rather than reviving her deceased chicks whom she herself murdered on account of their disobedience, in this depiction, the Good Pelican’s blood sustains her children and protects them from sin before their hearts are fully conquered by the Evil One. In congruence with later church theologians’ views on the legend, the Pelican’s blood is thus portrayed in the spiritually restorative manner of the Eucharistic Blood of Christ, exhorting the faithful to attend mass (and especially on a feast celebrating the triune God) and trust in the God-Man who could both heal the sick and raise from the dead.

Conclusion

Ultimately, although the Pelican In Her Piety motif evolved with shifting medieval attitudes toward the nature of Christ’s Passion and the redemption of the human race, it served since its inception as a conceptualization of Christ as a selfless, blameless servant, the Son of Man, determined to internally renew or revive the souls of the faithful in spite of all iniquity committed against him at the behest of God the Father, who formerly damned Man in the Garden and cursed the serpent to crawl upon the ground. Consequently, the pelican came to represent not only a symbol of this mission but also a general motif highlighting the nobility and virtue inherent in self-sacrifice, cohering nicely to the chivalric trends of knighthood at the time of the legend’s promulgation across the European Continent. In spite of its naturalistic inaccuracy, the Pelican in Her Piety epitomizes how even a flawed metaphorical representation can convey a deeper meaning to the Spirit, beyond the confines of empirical truth and the era in which it was composed.

(Cover Image: Unknown, Detail: A Pelican Feeding Her Young, Illuminated Manuscript Illustration, Europe, 1277 or after via Getty Museum.)