Analyzing how the techniques used in the earliest cave paintings reveal insights into human creative development and form the foundation for later artistic expression.

In the late Victorian era, England was at the height of its Industrial Revolution. Caught in a wave of sweeping mechanization, unprecedented production levels, and technological advancement, decorative artists working with textiles, ceramics, and furniture struggled to maintain influence in a rapidly changing world. The Arts and Crafts movement initially arose out of a desire to reform design, shifting away from factory production and instead placing emphasis on high-quality craftsmanship and illusionistic design, frequently inspired by nature and folk styles. The writer, John Ruskin, was a driving force behind the movement’s philosophy. He viewed art as a reflection of morality, criticizing the effects of the Industrial Revolution on craftsmanship—which he deemed a symptom of an increasingly corrupt society. William Morris, another well-known figure in the movement, brought his ideas into practice with his socialist activism and work with Morris & Co., reviving traditional textile artwork.

The work and ideas of Morris and Ruskin continued to grow in influence and have become quite popular and well-known today. However, since craft-related artwork, particularly embroidery, has not always been taken as seriously by art critics and historians in the past, many key figures have been overlooked. It is only recently that the work of other artists and activists has been illuminated. One of these artists was May Morris, the youngest daughter of William Morris, whose influential work has largely been overshadowed by that of her father. Born in 1862, she spent most of her childhood living above Morris & Co., where she was surrounded by other artists and learned the craft of embroidery from her mother and aunt. She began formal education at the National Art Training School in 1878, and four years later, at just twenty-three years old, she became the supervisor of Morris & Co.’s embroidery department.

Morris encouraged a collective approach to art-making, which embraced both amateurs and other professionals alike. Oftentimes, she would collaborate with other embroiderers to bring her designs to fruition, reminiscent of Renaissance workshops and guild collaboration. Perhaps this work environment inspired her to create the Women’s Guild of Arts in 1907, which encouraged artists, craftspeople, and architects by showcasing their work and hosting discussions. This was especially important considering that the Art Workers Guild excluded women until 1972. Morris also encouraged newcomers to the practice of embroidery, as she offered private embroidery lessons and also published a beginner’s guide: Decorative Needlework in 1893. In practice, amateur embroiderers could acquire embroidery kits from Morris & Co. to create designs such as Small Rose following one of Morris’ patterns.

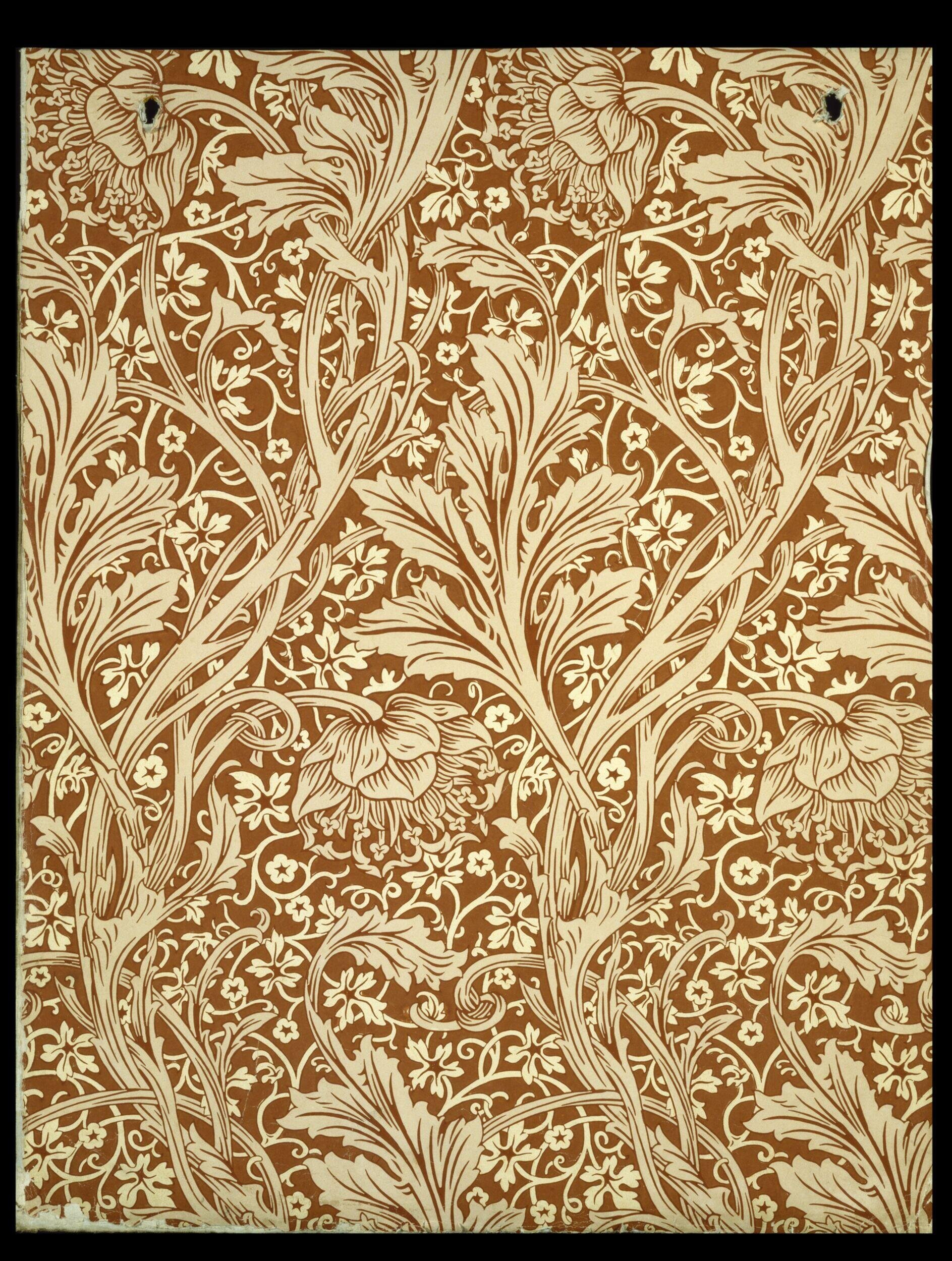

While her embroidery designs are most prolific, May Morris also contributed her artistic skills to her father’s famous wallpaper designs. Pictured below is one of her designs, titled Honeysuckle, which she completed in 1883. This was one of the firm’s most successful designs; its entwined stems and simple color palette perfectly encapsulate the Morris aesthetic as well as the Arts and Crafts movement as a whole. The authorship of this design has been historically contested, as it was originally attributed to William Morris himself in Women’s World, a Victorian women's magazine edited by Oscar Wilde. This was likely due to the fact that William Morris, being a more recognizable name, would have garnered more sales for the design than his daughter. Later letters written by May, as well as a Morris & Co. wallpaper catalogue, confirm that this is, in fact, her design.

Morris continually recalls the past in both her work’s material and subject matter. One such example are the Fruit Garden portières, completed between 1892 and 1893 and currently located at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Much inspiration is drawn from the medieval opus anglicanum style. The highly sought-after designs, produced in England from the twelfth century to the mid-fourteenth century, used gold threads, silk, and linen to create intricate, symmetrical designs frequently drawing upon nature for inspiration. The exquisite imagery utilized in opus anglicanum appears to be present within many of Morris’ designs, contrasting sharply with England’s modernized existence. Also notable is the panel’s inscription “Growth sed & blowth med & springeth wod nu,” taken from a thirteenth-century English folk song “Sumer is icumen in.” Medieval references such as these continue to percolate through her work, even after her departure from the Morris workshop.

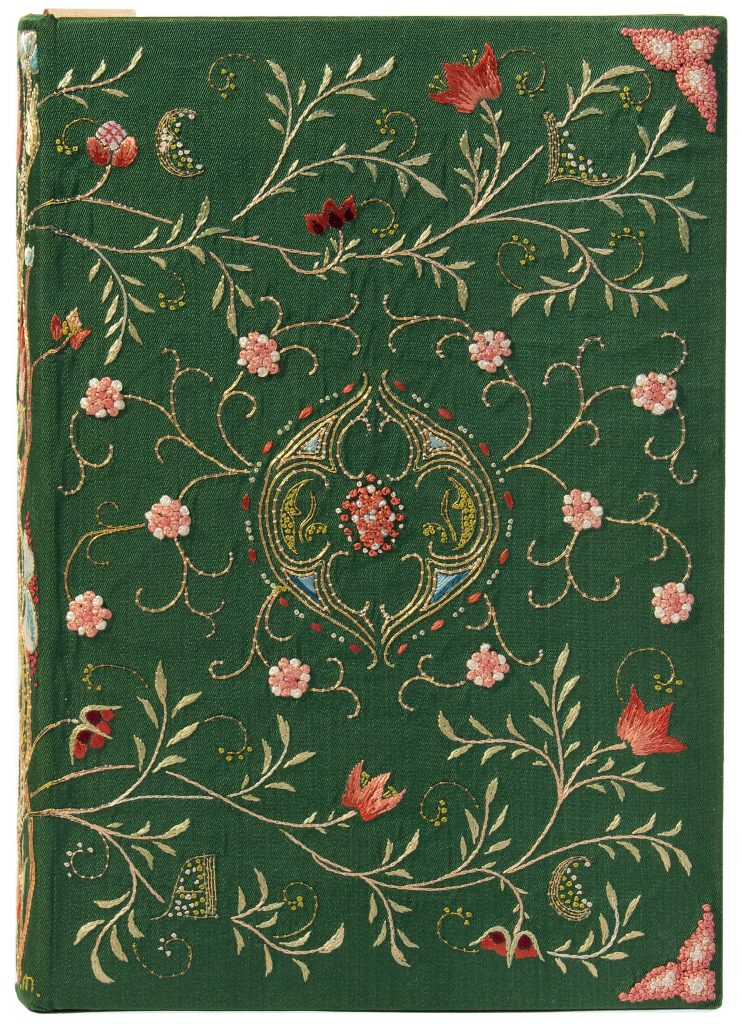

Not strictly confined to the Medieval period, her book cover and jewelry designs offer other connections to days gone by. The art of embroidered book bindings had waned over a century earlier, but in the late 1880s, Morris’ needlework helped to contribute to its renaissance. One such example is her binding for Ernest Lefébure’s Embroidery and Lace (1888), which encompasses an intricate design fitting of the book’s subject matter. The cover’s gold thread and small seed pearls contribute to this, with a symmetrical design and entwined stems that grow outwards from the spine and extend across to the front and back covers. The use of beadwork, though absent in much of her work for Morris & Co., was certainly not unfamiliar to her. Her jewelry designs indicate she was comfortable working with a wide array of gemstones. Included in one of her pendant designs, in addition to seed pearls, are amazonite, williamsite, and lapis lazuli in a heart-shaped form. The heart-shaped motif became increasingly popular during this time period, as it was frequently featured in traditional folk designs across Europe and Scandinavia. May Morris’ work with book bindings and jewelry broadened her expertise, further cementing her place as a key figure in the Arts and Crafts movement.

As a designer, embroiderer, and artist, May Morris had a significant influence on a movement that pushed the limits of what human hands can create, simultaneously a celebration of beauty and a protest of industrialism. Examining May’s work, we see clearly how looking towards the past remains a natural way to find ourselves in the future. The Morris approach is an increasingly topical reminder to savor the joy of creation and craft a way forward.

(Cover Image: Arcadia. Designed by May Morris, manufactured by Jeffery & Co. for Morris & Co., c. 1886. Block printed in distemper colour. Width 53.3 (21), pattern repeat 68 (26 ¾). V&A. Via V&A)